I am a Luxemburgist unlike Obama Barak

I am a Luxemburgist

Luxemburgism

Luxemburgism (also written Luxembourgism) is a specific revolutionary theory within Marxism and communism, based on the writings of Rosa Luxemburg. According to M. K. Dziewanowski, the term was originally coined by Bolshevik leaders denouncing the deviations of Luxemburg's followers from traditional Leninism, but it has since been adopted by her followers themselves.

Luxemburgism is an interpretation of Marxism which, while supporting the Russian Revolution, as Rosa Luxemburg did, agrees with her criticisms of the politics of Lenin and Trotsky; she did not see their concept of "democratic centralism" as democracy.

The chief tenets of Luxemburgism are committed to democracy and the necessity of the revolution taking place as soon as possible. In this regard, it is similar to Council Communism, but differs in that, for example, Luxemburgists do not reject elections by principle. It resembles anarchism in its insistence that only relying on the people themselves as opposed to their leaders can avoid an authoritarian society, but differs in that it sees the importance of a revolutionary party, and mainly the centrality of the working class in the revolutionary struggle. It resembles Trotskyism in its opposition to the totalitarianism of Stalinist government while simultaneously avoiding the reformist politics of Social Democracy, but differs from Trotskyism in arguing that Lenin and Trotsky also made undemocratic errors.

In "The Russian Revolution", written in a German jail during WWI, Luxemburg critiqued Bolsheviks' absolutist political practice and opportunist policies--i.e., their suppression of the Constituent Assembly in January 1918, their support for the partition of the old feudal estates to the peasant communes. She derived this critique from Marx's original concept of the "revolution in permanence." Marx outlines this strategy in his March 1850 "Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League." As opposed to the Bolsheviks neo-Blanquist interpretation of permanent revolution, Marx argued that the role of the working class revolutionary party was not to create a one-party state, nor to give away land--even in semi-feudal countries like Germany in 1850--or Russia in 1917--where the working class was in the minority.

Rather, Marx argued that the role of the working class was, WITHIN structures of radical democracy, to organize, arm and defend themselves in workers councils and militias, to campaign for their own socialist political program, to expand workers rights, and to seize and farm collectively the feudal estates. Because the Bolsheviks failed to fulfil this Marxian program, Luxemburg argued, the Revolution bureaucratized, the cities starved, the peasant soldiers in the Army were demoralized and deserted in order to get back home for the land grab. Thus the Germans easily invaded and took Ukraine. They justified this, during the Brest-Litovsk treaty negotiations, in the very same terms of "national self-determination" (for the Ukrainian bourgeoisie) that the Bolsheviks had promoted as an aid to socialist revolution, and that Luxemburg critiqued, years earlier, in her "The National Question," and in this document.

Luxemburg criticized Lenin's ideas on how to organize a revolutionary party as likely to lead to a loss of internal democracy and the domination of the party by a few leaders. Ironically, in her most famous attack on Lenin's views, the 1904 Organizational Questions of the Russian Social Democracy, or, Leninism or Marxism?,[1] a response to Lenin's 1903 What Is To Be Done?, Luxemburg was more worried that the authoritarianism she saw in Leninism would lead to sectarianism and irrelevancy than that it would lead to a dictatorship after a successful revolution - although she also warned of the latter danger. Luxemburg died before Stalin's assumption of power, and never had a chance to come up with a complete theory of Stalinism, but her criticisms of the Bolsheviks have been taken up by many writers in their arguments about the origins of Stalinism, including many who are otherwise far from Luxemburgism.

Luxemburg's idea of democracy, which Stanley Aronowitz calls "generalized democracy in an unarticulated form", represents Luxemburgism's greatest break with "mainstream communism", since it effectively diminishes the role of the Communist Party, but is in fact very similar to the views of Karl Marx ("The emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves"). According to Aronowitz, the vagueness of Luxembourgian democracy is one reason for its initial difficulty in gaining widespread support. However, since the fall of the Soviet Union, Luxemburgism has been seen by some socialist thinkers as a way to avoid the totalitarianism of Stalinism. Early on, Luxemburg attacked undemocratic tendencies present in the Russian Revolution:

Without general elections, without unrestricted freedom of press and assembly, without a free struggle of opinion, life dies out in every public institution, becomes a mere semblance of life, in which only the bureaucracy remains as the active element. Public life gradually falls asleep, a few dozen party leaders of inexhaustible energy and boundless experience direct and rule. Among them, in reality only a dozen outstanding heads do the leading and an elite of the working class is invited from time to time to meetings where they are to applaud the speeches of the leaders, and to approve proposed resolutions unanimously – at bottom, then, a clique affair – a dictatorship, to be sure, not the dictatorship of the proletariat but only the dictatorship of a handful of politicians, that is a dictatorship in the bourgeois sense, in the sense of the rule of the Jacobins (the postponement of the Soviet Congress from three-month periods to six-month periods!) Yes, we can go even further: such conditions must inevitably cause a brutalization of public life: attempted assassinations, shooting of hostages, etc. (Lenin's speech on discipline and corruption.)"[2]

The strategic contribution of Luxemburgism is principally based on her insistence on socialist democracy:

Freedom only for the supporters of the government, only for the members of one party – however numerous they may be – is no freedom at all. Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently. Not because of any fanatical concept of "justice" but because all that is instructive, wholesome and purifying in political freedom depends on this essential characteristic, and its effectiveness vanishes when "freedom" becomes a special privilege.(...)But socialist democracy is not something which begins only in the promised land after the foundations of socialist economy are created; it does not come as some sort of Christmas present for the worthy people who, in the interim, have loyally supported a handful of socialist dictators. Socialist democracy begins simultaneously with the beginnings of the destruction of class rule and of the construction of socialism."

The Dialectic of Spontaneity and Organisation was the central feature of Rosa Luxemburg's political philosophy, wherein "spontaneity" is a grass roots, even anarchistic, approach to organising a party-oriented class struggle. Spontaneity and organisation, she argued, are not separable or separate activities, but different moments of one political process; one does not exist without the other. These beliefs arose from her view that there is an elementary, spontaneous class struggle from which class struggle evolves to a higher level:

"The working classes in every country only learn to fight in the course of their struggles ... Social democracy ... is only the advance guard of the proletariat, a small piece of the total working masses; blood from their blood, and flesh from their flesh. Social democracy seeks and finds the ways, and particular slogans, of the workers' struggle only in the course of the development of this struggle, and gains directions for the way forward through this struggle alone."[4]

Organisation mediates spontaneity; organisation must mediate spontaneity. It would be wrong to accuse Rosa Luxemburg of holding "spontaneism" as an abstraction. She developed the Dialectic of Spontaneity and Organisation under the influence of mass strikes in Europe, especially the Russian Revolution of 1905. Unlike the social democratic orthodoxy of the Second International, she did not regard organisation as product of scientific-theoretic insight to historical imperatives, but as product of the working classes' struggles:

"Social democracy is simply the embodiment of the modern proletariat's class struggle, a struggle which is driven by a consciousness of its own historic consequences. The masses are in reality their own leaders, dialectically creating their own development process. The more that social democracy develops, grows, and becomes stronger, the more the enlightened masses of workers will take their own destinies, the leadership of their movement, and the determination of its direction into their own hands. And as the entire social democracy movement is only the conscious advance guard of the proletarian class movement, which in the words of the Communist Manifesto represent in every single moment of the struggle the permanent interests of liberation and the partial group interests of the workforce vis à vis the interests of the movement as whole, so within the social democracy its leaders are the more powerful, the more influential, the more clearly and consciously they make themselves merely the mouthpiece of the will and striving of the enlightened masses, merely the agents of the objective laws of the class movement."[5]

and

"The modern proletarian class does not carry out its struggle according to a plan set out in some book or theory; the modern workers' struggle is a part of history, a part of social progress, and in the middle of history, in the middle of progress, in the middle of the fight, we learn how we must fight... That's exactly what is laudable about it, that's exactly why this colossal piece of culture, within the modern workers' movement, is epoch-defining: that the great masses of the working people first forge from their own consciousness, from their own belief, and even from their own understanding the weapons of their own liberation."[6]

Other Luxemburg criticisms of Lenin and Trotsky

Rosa Luxemburg also criticized Lenin's views on the right of the oppressed nations of the former Czarist Empire to self-determination. She saw this as a ready-made formula for imperialist intervention in those countries on behalf of bourgeois forces hostile to socialism. Proponents of Lenin's position on the nationalities argue that it was in fact what brought many members of the different nationalities of the former Czarist Empire together in supporting the Bolshevik-led revolution.

Luxemburgism as opposition to imperialist war and capitalism

While being critical of the politics of the Bolsheviks, Rosa Luxemburg saw the behaviour of the Social Democratic Second International as a complete betrayal of socialism. As she saw it, at the outset of the First World War the Social Democratic Parties around the world betrayed the world's working class by supporting their own individual bourgeoisies in the war. This included her own Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), the majority of whose delegates in the Reichstag voted for war credits.

Rosa Luxemburg opposed the sending of the working class youth of each country to what she viewed as slaughter in a war over which of the national bourgeoisies would control world resources and markets. She broke from the Second International, viewing it as nothing more than an opportunist party that was doing administrative work for the capitalists. Rosa Luxemburg, with Karl Liebknecht, organized a strong movement in Germany with these views, but was imprisoned and, after her release, killed for her work during the failed German Revolution of 1919 - a revolution which the German Social Democratic Party violently opposed.

Present-day Luxemburgism

There are presently very few active Luxemburgist revolutionary movements. There are two small international networks that claim to be Luxemburgists : Communist Democracy (Luxemburgist), founded in 2005, and the International Luxemburgist Network, founded in 2008.

There is also widespread interest in her ideas particularly among feminists and Trotskyists as well as among leftists in Germany. It has been seen as a corrective to revolutionary theory by distinguished modern Marxist thinkers such as Ernest Mandel, who has even been characterised as "Luxemburgist".[7] In 2002 ten thousand people marched in Berlin for Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht and another 90,000 people laid carnations on their graves.[8]

To many socialists, whether they see themselves as Luxemburgist or not, Rosa Luxemburg was a martyr for revolutionary socialism. For Luxemburgists, her stalwart dedication to democracy and vigorous repudiation of capitalism exemplifies the socialist concept of democracy that is viewed as the essential element of socialism rather than a contradiction of it. Many socialist currents today, particularly Trotskyists, consider Rosa Luxemburg to have been an important influence on their theory and politics. However, while respecting Luxemburg, these organizations do not consider themselves "Luxemburgist."

Notable Luxemburgists

* Rosa Luxemburg

* Karl Liebknecht

* Paul Frölich

* René Lefeuvre

* Daniel Singer

* Alain Guillerm

* Eric Chester

* Ethem Nejat

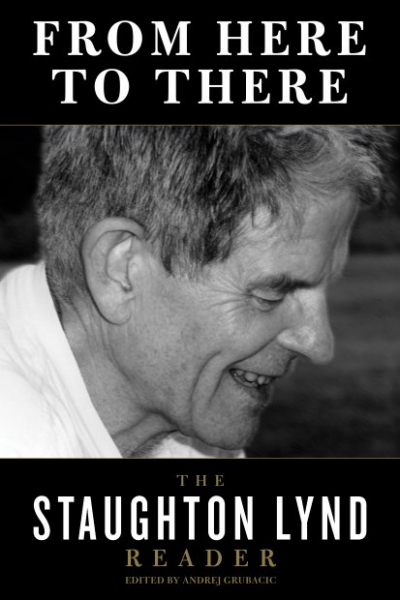

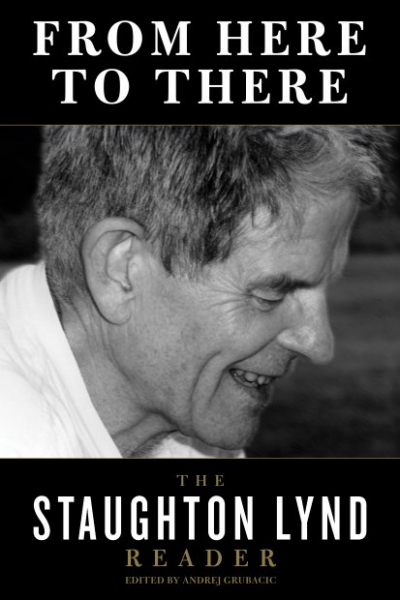

* Staughton Lynd

Staughton Lynd

Staughton Lynd (born November 22, 1929) is an American conscientious objector, quaker[1], peace activist and civil rights activist, tax resister, historian, professor, author and lawyer. His involvement in social justice causes has brought him into contact with some of the nation's most influential activists, including Howard Zinn, Tom Hayden and Daniel Berrigan.[2] Lynd's contribution to the cause of social justice and the peace movement is chronicled in Carl Mirra's biography, The Admirable Radical: Staughton Lynd and Cold War Dissent, 1945-1970, published in 2010 by Kent State University Press.

Early life

Lynd was one of two children born to the renowned sociologists Robert Staughton Lynd and Helen Lynd, who authored the groundbreaking "Middletown" studies of Muncie, Indiana, in the late 1920s and '30s. Staughton Lynd inherited not only his father's gifts as a scholar, but also his strong socialist beliefs. Although Lynd never embraced undemocratic forms of socialism, his ideological outlook led to his expulsion from a non-combatant position in the U.S. military during the McCarthy Era.

He went on to earn a doctorate in history at Columbia University and accepted a teaching position at Spelman College, in Georgia, where he became acquainted with historian and civil rights activist Howard Zinn. During the summer of 1964, Lynd served as director of the SNCC-organized Freedom Schools of Mississippi. After accepting a position at Yale University, Lynd relocated to New England, along with his wife, Alice, and their three children.

Vietnam-era activism

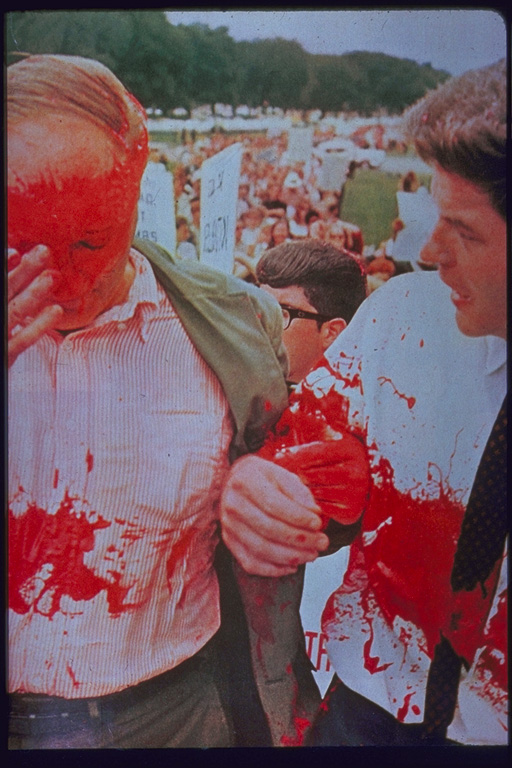

It was during his tenure at Yale that Lynd became an outspoken opponent of the Vietnam War.[2] His protest activities included speaking engagements, protest marches, and a controversial visit to Hanoi, which cost him his teaching position at Yale. As the protest movement became increasingly violent, Lynd began to have doubts about the values and practices of the New Left.[citation needed] As a self-described "social democratic pacifist", he became more interested in the possibilities of local organizing.

Labor activism

In the late 1960s, Lynd relocated his family to Chicago. There, he struggled to make a living from community organizing. Meanwhile, he and his wife, Alice, embarked upon an oral history project dealing with the working class. The conclusions of this work, titled Rank and File, inspired Lynd to study law in order to assist workers victimized by companies and left unprotected by declining labor unions. In 1973, he enrolled at the University of Chicago law school, where he earned a degree in 1976.

Rust Belt activism

From there, the Lynds relocated to Youngstown, Ohio, in the heart of the Rust Belt. He proved to be a vital participant in the late 1970s struggle to keep the Youngstown steel mills open. Despite the ultimate failure of those efforts, the Lynds have continued organizing in the Youngstown-Warren area.[3] Staughton Lynd has remained extremely active as an attorney, taking on a broad range of cases, including those concerning disabled and retired workers.

Lynd's book, Lucasville, is an investigation into the events surrounding the 1993 prison uprising at Southern Ohio Correctional Facility, and voices serious concern over the integrity of legal proceedings subsequent to the event. His newest book, a memoir of his and Alice's life, Stepping Stones: Memoir of a Life Together was released in January 2009.

Lynd still maintains an active Ohio law license.

THE FOLLOWING STATEMENT MADE BY ERIC CHESTER

John Olver has represented the First Congressional district of Massachusetts for eleven years. During this time he has become fully incorporated into the political establishment, a member of the House Appropriations Committee. Olver accepts tens of thousands of dollars from corporate PACs looking for special favors. He takes money from some of the largest corporations that benefit from wars and the military budget, corporations such as Raytheon, General Dynamics and General Electric.

Needless to say, Olver voted for the war, and for the increase in the military budget. Although he recently voted to oppose the PATRIOT Act, legislation that has eroded our fundamental civil liberties, he has remained silent in the face of the mass detentions, as well as the other abuses of basic rights that have occurred since September 11.

Western Massachusetts needs a representative in Congress who will do what is right, rather than what is expedient. I will propose an immediate 50% cut in the military budget, with the 175 billion dollars a year thus saved being used for essential social services. I will call for an immediate end to the blockade of Iraq and will urge an end to the Israeli occupation of the Occupied Territories. I will oppose further military aid to Israel. I will propose that the United States withdraw from all overseas military bases, most especially Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, and that the U.S. Navy immediately withdraw from the Vieques base in Puerto Rico. *

I will also challenge corporate power by proposing a steep tax on high incomes and large estates. I will oppose the expansion of the free trade zone to South America, and an end to the current one covering North America. I will call for an economic program that will create millions of full-time union jobs in the public sector, jobs such as child care educators, teachers, professors, nurses, construction workers and bus drivers. We need to do all this, but we need to do much more.

The United States is in the midst of a deepening crisis. Since September 11, U.S. troops have invaded and occupied Afghanistan, and there is every reason to expect that other military actions will soon follow, all taken under the cover of the 'war against terrorism.' The corporate mass media continues to whip up a wartime hysteria, as politicians from both mainstream political parties try to outdo each other in their jingoistic support for more wars.

Civil liberties have been sharply curtailed, as the government uses widespread fear to expand its repressive powers. More than a thousand immigrants, mostly from the Middle East, have been held for months on the flimsiest of pretexts, in secret and without reasonable grounds for suspicion. The United States has also flaunted the Geneva agreement on prisoners of war in its mistreatment of those captured in Afghanistan.

The already bloated military budget has swelled by another forty billion dollars, with further increases on tap. At the same time, spending on vital social services is being drastically cut, so that essential programs such as education, child care, health care, low-cost housing and mass transit starve for lack of funds while the military booms.

Even before September 11, the economy was moving downward. Since then,

we have entered into a major slump, one of the most severe since the Great

Depression of the 1930s. Yet the government has done little to counteract

unemployment, relying on more tax breaks for the rich to stimulate the

economy.

All of these recent events come as a handful of huge and powerful corporations continue their drive to control the wealth and resources of the entire planet. In doing so, they act to destroy the environment and crush trade unions. Old industrial centers, such as Holyoke, Pittsfield and Greenfield, are left to rot. Around the world, the gulf between the rich and poor has widened. Millions sleep in the streets or live in squalid slums while a few individuals acquire a *personal wealth in the tens of billions of dollars. *

As long as a few powerful corporations dominate the global economy, we will continue to live in a society marked by poverty and violence. Changing this will require a massive social movement that can shake the foundations of the current system. Such a movement will of necessity advance an independent politics as it challenges the two party system. For too long, working people and those who seek social change have settled for the lesser evil. Both mainstream political parties are funded and controlled by the big corporations. Voting for Democrats is a dead end. It is time for all

those committed to a just world to make a definitive break with both the

Democrats and the Republicans. *

Ultimately, only a democratic socialist transformation can move us out of the current impasse. Workers control, cooperation, grass-roots democracy, equality and social justice must replace competition, poverty and hierarchy. Instead of a capitalist market economy driven by production for profit we need to rapidly move toward a cooperative economy based on production for need through decentralized planning. My campaign can only provide one small step in this transformation toward a new society, and yet an important one.

ERIC CHESTER FOR CONGRESS

43 Taylor Hill Road

*Montague, MA. 01351

(413) 367-9356 or chesterforcongress2002@hotmail.com

Eric Thomas Chester (born 6 August 1943) is an author, socialist political activist, and former economics professor.

Born in New York City, he is the son of Harry (a UAW economist) and Alice (a psychiatrist née Fried) Chester. Both parents were active socialists from Vienna, opposing the rise of fascism and nazism.

Chester was a member of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) while at the University of Michigan in the 1960s, when he opposed the war in Vietnam. He was a member of New American Movement in the 1970s, and has been a member of the Socialist Party USA since 1980. He helped organize the faculty union while teaching at the University of Massachusetts Boston. He is currently a member of the National Writers Union (UAW), an active member in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), the Socialist Party of Massachusetts, and the Socialist Party USA, and was the Socialist Party USA's candidate for Vice President in 1996. The 1996 Socialist Party USA presidential ticket of Mary Cal Hollis and Chester received 4,765 votes[1]. He campaigned for the SP's Presidential nomination for the 2000, 2004 and 2008 elections, but lost to David McReynolds, Walt Brown and Brian Moore, respectively.[2][3] He twice ran for Congress from Massachusetts's First Congressional District, in 2002 and 2006.

Chester taught economics at the University of Massachusetts Boston (1973–1978; 1986) and San Francisco State University (1981). He has published four books, focusing especially on "the hidden secrets of U.S. foreign policy" and "the connections between U.S. foreign policy and social democrats, in this country and abroad".[4] In an interview with Contemporary Authors, he described the resulting difficulties in archival research, "the search for previously undiscovered primary source documents", and often a declassification process that "usually entails extended appeals as provided for under the Freedom of Information Act." Chester is unwilling to rely on the public record, and urges researchers "to probe beneath the surface" and keep in mind that "the goals and actions of decision makers, as well as their envoys, are frequently in marked contrast to their public statements."[4]

As of 2007, Chester is Convener of the International Commission of the Socialist Party USA. In 2006-2007 he also served as a member of the International Solidarity Committee of the IWW. He advocates supporting and uniting the new radical and revolutionary anti-capitalist movements that are being generated by the conditions of worldwide economic globalization of capitalism, into a mass revolutionary socialist party that is independent of the two capitalist parties, the Democratic and Republican Parties. Following the principles and ideas of Eugene V. Debs and Rosa Luxemburg, he describes himself as a revolutionary democratic socialist.

He currently lives in Montague, Massachusetts.

* True Mission: Socialists and the Labor Party Question in the U.S., ISBN 0-7453-2215-8, Pluto Press, 2004.

* Rag-Tags, Scum, Riff-Raff and Commies: The U.S. Intervention in the Dominican Republic, 1965-1966, ISBN 1-58367-032-7, New York University Press, 2001.

* Covert Network: Progressives, the International Rescue Committee, and the CIA, ISBN 1-56324-551-5, M. E. Sharpe, 1995.

* Socialists and the Ballot Box, ISBN 0-03-004142-2, Praeger Publishers, 1985.

* Article contributions to Public Finance, Cambridge Journal of Economics, Insurgent Sociologist, New Politics, Against the Current, and The Socialist.

Luxemburgism

Luxemburgism (also written Luxembourgism) is a specific revolutionary theory within Marxism and communism, based on the writings of Rosa Luxemburg. According to M. K. Dziewanowski, the term was originally coined by Bolshevik leaders denouncing the deviations of Luxemburg's followers from traditional Leninism, but it has since been adopted by her followers themselves.

Luxemburgism is an interpretation of Marxism which, while supporting the Russian Revolution, as Rosa Luxemburg did, agrees with her criticisms of the politics of Lenin and Trotsky; she did not see their concept of "democratic centralism" as democracy.

The chief tenets of Luxemburgism are committed to democracy and the necessity of the revolution taking place as soon as possible. In this regard, it is similar to Council Communism, but differs in that, for example, Luxemburgists do not reject elections by principle. It resembles anarchism in its insistence that only relying on the people themselves as opposed to their leaders can avoid an authoritarian society, but differs in that it sees the importance of a revolutionary party, and mainly the centrality of the working class in the revolutionary struggle. It resembles Trotskyism in its opposition to the totalitarianism of Stalinist government while simultaneously avoiding the reformist politics of Social Democracy, but differs from Trotskyism in arguing that Lenin and Trotsky also made undemocratic errors.

In "The Russian Revolution", written in a German jail during WWI, Luxemburg critiqued Bolsheviks' absolutist political practice and opportunist policies--i.e., their suppression of the Constituent Assembly in January 1918, their support for the partition of the old feudal estates to the peasant communes. She derived this critique from Marx's original concept of the "revolution in permanence." Marx outlines this strategy in his March 1850 "Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League." As opposed to the Bolsheviks neo-Blanquist interpretation of permanent revolution, Marx argued that the role of the working class revolutionary party was not to create a one-party state, nor to give away land--even in semi-feudal countries like Germany in 1850--or Russia in 1917--where the working class was in the minority.

Rather, Marx argued that the role of the working class was, WITHIN structures of radical democracy, to organize, arm and defend themselves in workers councils and militias, to campaign for their own socialist political program, to expand workers rights, and to seize and farm collectively the feudal estates. Because the Bolsheviks failed to fulfil this Marxian program, Luxemburg argued, the Revolution bureaucratized, the cities starved, the peasant soldiers in the Army were demoralized and deserted in order to get back home for the land grab. Thus the Germans easily invaded and took Ukraine. They justified this, during the Brest-Litovsk treaty negotiations, in the very same terms of "national self-determination" (for the Ukrainian bourgeoisie) that the Bolsheviks had promoted as an aid to socialist revolution, and that Luxemburg critiqued, years earlier, in her "The National Question," and in this document.

Luxemburg criticized Lenin's ideas on how to organize a revolutionary party as likely to lead to a loss of internal democracy and the domination of the party by a few leaders. Ironically, in her most famous attack on Lenin's views, the 1904 Organizational Questions of the Russian Social Democracy, or, Leninism or Marxism?,[1] a response to Lenin's 1903 What Is To Be Done?, Luxemburg was more worried that the authoritarianism she saw in Leninism would lead to sectarianism and irrelevancy than that it would lead to a dictatorship after a successful revolution - although she also warned of the latter danger. Luxemburg died before Stalin's assumption of power, and never had a chance to come up with a complete theory of Stalinism, but her criticisms of the Bolsheviks have been taken up by many writers in their arguments about the origins of Stalinism, including many who are otherwise far from Luxemburgism.

Luxemburg's idea of democracy, which Stanley Aronowitz calls "generalized democracy in an unarticulated form", represents Luxemburgism's greatest break with "mainstream communism", since it effectively diminishes the role of the Communist Party, but is in fact very similar to the views of Karl Marx ("The emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves"). According to Aronowitz, the vagueness of Luxembourgian democracy is one reason for its initial difficulty in gaining widespread support. However, since the fall of the Soviet Union, Luxemburgism has been seen by some socialist thinkers as a way to avoid the totalitarianism of Stalinism. Early on, Luxemburg attacked undemocratic tendencies present in the Russian Revolution:

Without general elections, without unrestricted freedom of press and assembly, without a free struggle of opinion, life dies out in every public institution, becomes a mere semblance of life, in which only the bureaucracy remains as the active element. Public life gradually falls asleep, a few dozen party leaders of inexhaustible energy and boundless experience direct and rule. Among them, in reality only a dozen outstanding heads do the leading and an elite of the working class is invited from time to time to meetings where they are to applaud the speeches of the leaders, and to approve proposed resolutions unanimously – at bottom, then, a clique affair – a dictatorship, to be sure, not the dictatorship of the proletariat but only the dictatorship of a handful of politicians, that is a dictatorship in the bourgeois sense, in the sense of the rule of the Jacobins (the postponement of the Soviet Congress from three-month periods to six-month periods!) Yes, we can go even further: such conditions must inevitably cause a brutalization of public life: attempted assassinations, shooting of hostages, etc. (Lenin's speech on discipline and corruption.)"[2]

The strategic contribution of Luxemburgism is principally based on her insistence on socialist democracy:

Freedom only for the supporters of the government, only for the members of one party – however numerous they may be – is no freedom at all. Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently. Not because of any fanatical concept of "justice" but because all that is instructive, wholesome and purifying in political freedom depends on this essential characteristic, and its effectiveness vanishes when "freedom" becomes a special privilege.(...)But socialist democracy is not something which begins only in the promised land after the foundations of socialist economy are created; it does not come as some sort of Christmas present for the worthy people who, in the interim, have loyally supported a handful of socialist dictators. Socialist democracy begins simultaneously with the beginnings of the destruction of class rule and of the construction of socialism."

The Dialectic of Spontaneity and Organisation was the central feature of Rosa Luxemburg's political philosophy, wherein "spontaneity" is a grass roots, even anarchistic, approach to organising a party-oriented class struggle. Spontaneity and organisation, she argued, are not separable or separate activities, but different moments of one political process; one does not exist without the other. These beliefs arose from her view that there is an elementary, spontaneous class struggle from which class struggle evolves to a higher level:

"The working classes in every country only learn to fight in the course of their struggles ... Social democracy ... is only the advance guard of the proletariat, a small piece of the total working masses; blood from their blood, and flesh from their flesh. Social democracy seeks and finds the ways, and particular slogans, of the workers' struggle only in the course of the development of this struggle, and gains directions for the way forward through this struggle alone."[4]

Organisation mediates spontaneity; organisation must mediate spontaneity. It would be wrong to accuse Rosa Luxemburg of holding "spontaneism" as an abstraction. She developed the Dialectic of Spontaneity and Organisation under the influence of mass strikes in Europe, especially the Russian Revolution of 1905. Unlike the social democratic orthodoxy of the Second International, she did not regard organisation as product of scientific-theoretic insight to historical imperatives, but as product of the working classes' struggles:

"Social democracy is simply the embodiment of the modern proletariat's class struggle, a struggle which is driven by a consciousness of its own historic consequences. The masses are in reality their own leaders, dialectically creating their own development process. The more that social democracy develops, grows, and becomes stronger, the more the enlightened masses of workers will take their own destinies, the leadership of their movement, and the determination of its direction into their own hands. And as the entire social democracy movement is only the conscious advance guard of the proletarian class movement, which in the words of the Communist Manifesto represent in every single moment of the struggle the permanent interests of liberation and the partial group interests of the workforce vis à vis the interests of the movement as whole, so within the social democracy its leaders are the more powerful, the more influential, the more clearly and consciously they make themselves merely the mouthpiece of the will and striving of the enlightened masses, merely the agents of the objective laws of the class movement."[5]

and

"The modern proletarian class does not carry out its struggle according to a plan set out in some book or theory; the modern workers' struggle is a part of history, a part of social progress, and in the middle of history, in the middle of progress, in the middle of the fight, we learn how we must fight... That's exactly what is laudable about it, that's exactly why this colossal piece of culture, within the modern workers' movement, is epoch-defining: that the great masses of the working people first forge from their own consciousness, from their own belief, and even from their own understanding the weapons of their own liberation."[6]

Other Luxemburg criticisms of Lenin and Trotsky

Rosa Luxemburg also criticized Lenin's views on the right of the oppressed nations of the former Czarist Empire to self-determination. She saw this as a ready-made formula for imperialist intervention in those countries on behalf of bourgeois forces hostile to socialism. Proponents of Lenin's position on the nationalities argue that it was in fact what brought many members of the different nationalities of the former Czarist Empire together in supporting the Bolshevik-led revolution.

Luxemburgism as opposition to imperialist war and capitalism

While being critical of the politics of the Bolsheviks, Rosa Luxemburg saw the behaviour of the Social Democratic Second International as a complete betrayal of socialism. As she saw it, at the outset of the First World War the Social Democratic Parties around the world betrayed the world's working class by supporting their own individual bourgeoisies in the war. This included her own Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), the majority of whose delegates in the Reichstag voted for war credits.

Rosa Luxemburg opposed the sending of the working class youth of each country to what she viewed as slaughter in a war over which of the national bourgeoisies would control world resources and markets. She broke from the Second International, viewing it as nothing more than an opportunist party that was doing administrative work for the capitalists. Rosa Luxemburg, with Karl Liebknecht, organized a strong movement in Germany with these views, but was imprisoned and, after her release, killed for her work during the failed German Revolution of 1919 - a revolution which the German Social Democratic Party violently opposed.

Present-day Luxemburgism

There are presently very few active Luxemburgist revolutionary movements. There are two small international networks that claim to be Luxemburgists : Communist Democracy (Luxemburgist), founded in 2005, and the International Luxemburgist Network, founded in 2008.

There is also widespread interest in her ideas particularly among feminists and Trotskyists as well as among leftists in Germany. It has been seen as a corrective to revolutionary theory by distinguished modern Marxist thinkers such as Ernest Mandel, who has even been characterised as "Luxemburgist".[7] In 2002 ten thousand people marched in Berlin for Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht and another 90,000 people laid carnations on their graves.[8]

To many socialists, whether they see themselves as Luxemburgist or not, Rosa Luxemburg was a martyr for revolutionary socialism. For Luxemburgists, her stalwart dedication to democracy and vigorous repudiation of capitalism exemplifies the socialist concept of democracy that is viewed as the essential element of socialism rather than a contradiction of it. Many socialist currents today, particularly Trotskyists, consider Rosa Luxemburg to have been an important influence on their theory and politics. However, while respecting Luxemburg, these organizations do not consider themselves "Luxemburgist."

Notable Luxemburgists

* Rosa Luxemburg

* Karl Liebknecht

* Paul Frölich

* René Lefeuvre

* Daniel Singer

* Alain Guillerm

* Eric Chester

* Ethem Nejat

* Staughton Lynd

Staughton Lynd

Staughton Lynd (born November 22, 1929) is an American conscientious objector, quaker[1], peace activist and civil rights activist, tax resister, historian, professor, author and lawyer. His involvement in social justice causes has brought him into contact with some of the nation's most influential activists, including Howard Zinn, Tom Hayden and Daniel Berrigan.[2] Lynd's contribution to the cause of social justice and the peace movement is chronicled in Carl Mirra's biography, The Admirable Radical: Staughton Lynd and Cold War Dissent, 1945-1970, published in 2010 by Kent State University Press.

Early life

Lynd was one of two children born to the renowned sociologists Robert Staughton Lynd and Helen Lynd, who authored the groundbreaking "Middletown" studies of Muncie, Indiana, in the late 1920s and '30s. Staughton Lynd inherited not only his father's gifts as a scholar, but also his strong socialist beliefs. Although Lynd never embraced undemocratic forms of socialism, his ideological outlook led to his expulsion from a non-combatant position in the U.S. military during the McCarthy Era.

He went on to earn a doctorate in history at Columbia University and accepted a teaching position at Spelman College, in Georgia, where he became acquainted with historian and civil rights activist Howard Zinn. During the summer of 1964, Lynd served as director of the SNCC-organized Freedom Schools of Mississippi. After accepting a position at Yale University, Lynd relocated to New England, along with his wife, Alice, and their three children.

Vietnam-era activism

It was during his tenure at Yale that Lynd became an outspoken opponent of the Vietnam War.[2] His protest activities included speaking engagements, protest marches, and a controversial visit to Hanoi, which cost him his teaching position at Yale. As the protest movement became increasingly violent, Lynd began to have doubts about the values and practices of the New Left.[citation needed] As a self-described "social democratic pacifist", he became more interested in the possibilities of local organizing.

Labor activism

In the late 1960s, Lynd relocated his family to Chicago. There, he struggled to make a living from community organizing. Meanwhile, he and his wife, Alice, embarked upon an oral history project dealing with the working class. The conclusions of this work, titled Rank and File, inspired Lynd to study law in order to assist workers victimized by companies and left unprotected by declining labor unions. In 1973, he enrolled at the University of Chicago law school, where he earned a degree in 1976.

Rust Belt activism

From there, the Lynds relocated to Youngstown, Ohio, in the heart of the Rust Belt. He proved to be a vital participant in the late 1970s struggle to keep the Youngstown steel mills open. Despite the ultimate failure of those efforts, the Lynds have continued organizing in the Youngstown-Warren area.[3] Staughton Lynd has remained extremely active as an attorney, taking on a broad range of cases, including those concerning disabled and retired workers.

Lynd's book, Lucasville, is an investigation into the events surrounding the 1993 prison uprising at Southern Ohio Correctional Facility, and voices serious concern over the integrity of legal proceedings subsequent to the event. His newest book, a memoir of his and Alice's life, Stepping Stones: Memoir of a Life Together was released in January 2009.

Lynd still maintains an active Ohio law license.

THE FOLLOWING STATEMENT MADE BY ERIC CHESTER

John Olver has represented the First Congressional district of Massachusetts for eleven years. During this time he has become fully incorporated into the political establishment, a member of the House Appropriations Committee. Olver accepts tens of thousands of dollars from corporate PACs looking for special favors. He takes money from some of the largest corporations that benefit from wars and the military budget, corporations such as Raytheon, General Dynamics and General Electric.

Needless to say, Olver voted for the war, and for the increase in the military budget. Although he recently voted to oppose the PATRIOT Act, legislation that has eroded our fundamental civil liberties, he has remained silent in the face of the mass detentions, as well as the other abuses of basic rights that have occurred since September 11.

Western Massachusetts needs a representative in Congress who will do what is right, rather than what is expedient. I will propose an immediate 50% cut in the military budget, with the 175 billion dollars a year thus saved being used for essential social services. I will call for an immediate end to the blockade of Iraq and will urge an end to the Israeli occupation of the Occupied Territories. I will oppose further military aid to Israel. I will propose that the United States withdraw from all overseas military bases, most especially Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, and that the U.S. Navy immediately withdraw from the Vieques base in Puerto Rico. *

I will also challenge corporate power by proposing a steep tax on high incomes and large estates. I will oppose the expansion of the free trade zone to South America, and an end to the current one covering North America. I will call for an economic program that will create millions of full-time union jobs in the public sector, jobs such as child care educators, teachers, professors, nurses, construction workers and bus drivers. We need to do all this, but we need to do much more.

The United States is in the midst of a deepening crisis. Since September 11, U.S. troops have invaded and occupied Afghanistan, and there is every reason to expect that other military actions will soon follow, all taken under the cover of the 'war against terrorism.' The corporate mass media continues to whip up a wartime hysteria, as politicians from both mainstream political parties try to outdo each other in their jingoistic support for more wars.

Civil liberties have been sharply curtailed, as the government uses widespread fear to expand its repressive powers. More than a thousand immigrants, mostly from the Middle East, have been held for months on the flimsiest of pretexts, in secret and without reasonable grounds for suspicion. The United States has also flaunted the Geneva agreement on prisoners of war in its mistreatment of those captured in Afghanistan.

The already bloated military budget has swelled by another forty billion dollars, with further increases on tap. At the same time, spending on vital social services is being drastically cut, so that essential programs such as education, child care, health care, low-cost housing and mass transit starve for lack of funds while the military booms.

Even before September 11, the economy was moving downward. Since then,

we have entered into a major slump, one of the most severe since the Great

Depression of the 1930s. Yet the government has done little to counteract

unemployment, relying on more tax breaks for the rich to stimulate the

economy.

All of these recent events come as a handful of huge and powerful corporations continue their drive to control the wealth and resources of the entire planet. In doing so, they act to destroy the environment and crush trade unions. Old industrial centers, such as Holyoke, Pittsfield and Greenfield, are left to rot. Around the world, the gulf between the rich and poor has widened. Millions sleep in the streets or live in squalid slums while a few individuals acquire a *personal wealth in the tens of billions of dollars. *

As long as a few powerful corporations dominate the global economy, we will continue to live in a society marked by poverty and violence. Changing this will require a massive social movement that can shake the foundations of the current system. Such a movement will of necessity advance an independent politics as it challenges the two party system. For too long, working people and those who seek social change have settled for the lesser evil. Both mainstream political parties are funded and controlled by the big corporations. Voting for Democrats is a dead end. It is time for all

those committed to a just world to make a definitive break with both the

Democrats and the Republicans. *

Ultimately, only a democratic socialist transformation can move us out of the current impasse. Workers control, cooperation, grass-roots democracy, equality and social justice must replace competition, poverty and hierarchy. Instead of a capitalist market economy driven by production for profit we need to rapidly move toward a cooperative economy based on production for need through decentralized planning. My campaign can only provide one small step in this transformation toward a new society, and yet an important one.

ERIC CHESTER FOR CONGRESS

43 Taylor Hill Road

*Montague, MA. 01351

(413) 367-9356 or chesterforcongress2002@hotmail.com

Eric Thomas Chester (born 6 August 1943) is an author, socialist political activist, and former economics professor.

Born in New York City, he is the son of Harry (a UAW economist) and Alice (a psychiatrist née Fried) Chester. Both parents were active socialists from Vienna, opposing the rise of fascism and nazism.

Chester was a member of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) while at the University of Michigan in the 1960s, when he opposed the war in Vietnam. He was a member of New American Movement in the 1970s, and has been a member of the Socialist Party USA since 1980. He helped organize the faculty union while teaching at the University of Massachusetts Boston. He is currently a member of the National Writers Union (UAW), an active member in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), the Socialist Party of Massachusetts, and the Socialist Party USA, and was the Socialist Party USA's candidate for Vice President in 1996. The 1996 Socialist Party USA presidential ticket of Mary Cal Hollis and Chester received 4,765 votes[1]. He campaigned for the SP's Presidential nomination for the 2000, 2004 and 2008 elections, but lost to David McReynolds, Walt Brown and Brian Moore, respectively.[2][3] He twice ran for Congress from Massachusetts's First Congressional District, in 2002 and 2006.

Chester taught economics at the University of Massachusetts Boston (1973–1978; 1986) and San Francisco State University (1981). He has published four books, focusing especially on "the hidden secrets of U.S. foreign policy" and "the connections between U.S. foreign policy and social democrats, in this country and abroad".[4] In an interview with Contemporary Authors, he described the resulting difficulties in archival research, "the search for previously undiscovered primary source documents", and often a declassification process that "usually entails extended appeals as provided for under the Freedom of Information Act." Chester is unwilling to rely on the public record, and urges researchers "to probe beneath the surface" and keep in mind that "the goals and actions of decision makers, as well as their envoys, are frequently in marked contrast to their public statements."[4]

As of 2007, Chester is Convener of the International Commission of the Socialist Party USA. In 2006-2007 he also served as a member of the International Solidarity Committee of the IWW. He advocates supporting and uniting the new radical and revolutionary anti-capitalist movements that are being generated by the conditions of worldwide economic globalization of capitalism, into a mass revolutionary socialist party that is independent of the two capitalist parties, the Democratic and Republican Parties. Following the principles and ideas of Eugene V. Debs and Rosa Luxemburg, he describes himself as a revolutionary democratic socialist.

He currently lives in Montague, Massachusetts.

* True Mission: Socialists and the Labor Party Question in the U.S., ISBN 0-7453-2215-8, Pluto Press, 2004.

* Rag-Tags, Scum, Riff-Raff and Commies: The U.S. Intervention in the Dominican Republic, 1965-1966, ISBN 1-58367-032-7, New York University Press, 2001.

* Covert Network: Progressives, the International Rescue Committee, and the CIA, ISBN 1-56324-551-5, M. E. Sharpe, 1995.

* Socialists and the Ballot Box, ISBN 0-03-004142-2, Praeger Publishers, 1985.

* Article contributions to Public Finance, Cambridge Journal of Economics, Insurgent Sociologist, New Politics, Against the Current, and The Socialist.

Earth's magnetic field:

Earth's magnetic field:

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home