US coup d'etat 1933

By John Spivak

The following article is an edited version of two chapters from John Spivak's autobiography (A Man in His Time, 1967).

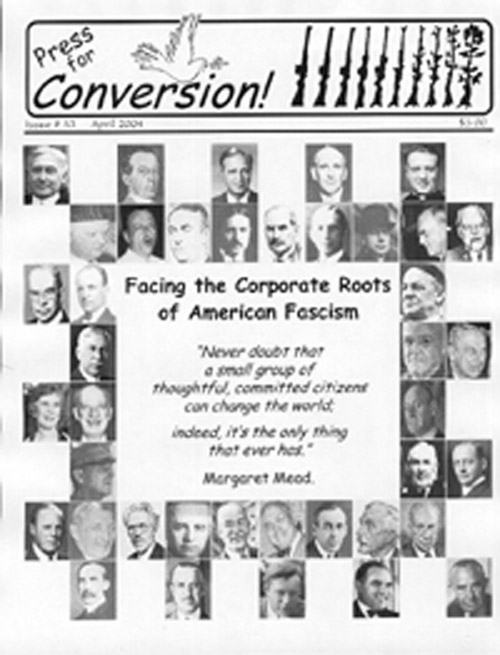

All of the photos and links on this web site were added to John Spivak's work by Richard Sanders, editor of Press for Conversion!, quarterly magazine of the Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade (COAT).

This site is a web version of "Facing the Corporate Roots of American Fascism," issue #53 of Press for Conversion! (April 2004). A hard copy of this 54-page magazine can be ordered from COAT. (Click here for details on how to order.)

Around the beginning of July 1933, the first overt move was made in one of the most fantastic plots in American history. A representative of a group of conspirators opened negotiations with a noted military man to head a 500,000-man army, seize the Government of the United States, put an end to American democracy and supplant it with a dictatorship. The McCormack-Dickstein House Committee, investigating un-American activities, turned its attention to the plot, but that probe ended abruptly. Even a generation later, those who are still alive and know all the facts have kept their silence so well that the conspiracy is not even a footnote in American histories. It would be regrettable if historians neglected this episode and future generations never learned of it.

Around the beginning of July 1933, the first overt move was made in one of the most fantastic plots in American history. A representative of a group of conspirators opened negotiations with a noted military man to head a 500,000-man army, seize the Government of the United States, put an end to American democracy and supplant it with a dictatorship. The McCormack-Dickstein House Committee, investigating un-American activities, turned its attention to the plot, but that probe ended abruptly. Even a generation later, those who are still alive and know all the facts have kept their silence so well that the conspiracy is not even a footnote in American histories. It would be regrettable if historians neglected this episode and future generations never learned of it.

When the plot actually began, or whose inspiration it was, is not known, for the Committee avoided probing into these aspects. News of the plot, reported to have backing of "three million dollars on the line and three hundred million...should it be necessary," reached the nation in a time which saw greater changes in political systems than any previous period.

The takeover plot failed because although those involved had astonishing talents for making breathtaking millions of dollars, they lacked an elementary understanding of people and the moral forces that activate them. In a money-standard civilization such as ours, the universal regard for anyone who is rich tends to persuade some millionaires that they are knowledgeable in fields other than the making of money. The conspirators went about the plot as if they were hiring an office manager; all they needed was to send a messenger to the man they had selected. In this case, as recorded in sworn testimony before the Congressional Committee, the messenger was a bond salesman named Gerald C. ("Jerry") MacGuire, who earned about $150 a week. I record his wage not as proof of his competence or lack of it, but because, as brought out in the testimony, when he was ready for the first overt move to get the conspiracy off the ground, his bank account flowered with cash deposits of over $100,000 for "expenses."

The takeover plot failed because although those involved had astonishing talents for making breathtaking millions of dollars, they lacked an elementary understanding of people and the moral forces that activate them. In a money-standard civilization such as ours, the universal regard for anyone who is rich tends to persuade some millionaires that they are knowledgeable in fields other than the making of money. The conspirators went about the plot as if they were hiring an office manager; all they needed was to send a messenger to the man they had selected. In this case, as recorded in sworn testimony before the Congressional Committee, the messenger was a bond salesman named Gerald C. ("Jerry") MacGuire, who earned about $150 a week. I record his wage not as proof of his competence or lack of it, but because, as brought out in the testimony, when he was ready for the first overt move to get the conspiracy off the ground, his bank account flowered with cash deposits of over $100,000 for "expenses."

MacGuire was a short, stocky man tending toward three chins. His bullet-shaped head had a silver plate in it due to a wound received in battle. His close-cropped hair was usually topped by a black derby, the popular headgear of the day. A reporter described his bright blue eyes as glittering with the sharpness of a fox about to spring.

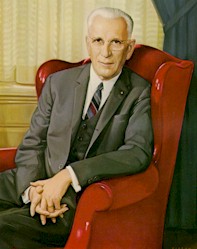

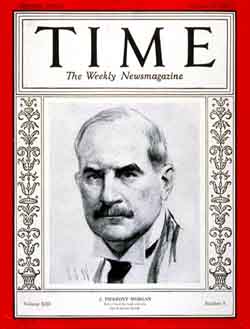

MacGuire worked for a leading brokerage house headed by Grayson Mallet-Prevost Murphy, a West Point graduate who had seen action in the Spanish-American War and WWI. Murphy had extensive industrial and financial interests as a director of Anaconda, Goodyear Tire, Bethlehem Steel and a number of Morgan-controlled banks. His personal appearance was impressive: tall, heavy-set and giving evidence that in his younger years, he must have been quite handsome.

MacGuire worked for a leading brokerage house headed by Grayson Mallet-Prevost Murphy, a West Point graduate who had seen action in the Spanish-American War and WWI. Murphy had extensive industrial and financial interests as a director of Anaconda, Goodyear Tire, Bethlehem Steel and a number of Morgan-controlled banks. His personal appearance was impressive: tall, heavy-set and giving evidence that in his younger years, he must have been quite handsome.

I heard rumors [of the fascist plot] in Washington more than a month before news of it broke. The talk was that the American Legion would be the nucleus for a fascist army which would seize Washington. Even in a city notorious as a gossip center, this sounded like something out of a Central American "banana republic."

I heard rumors [of the fascist plot] in Washington more than a month before news of it broke. The talk was that the American Legion would be the nucleus for a fascist army which would seize Washington. Even in a city notorious as a gossip center, this sounded like something out of a Central American "banana republic."

According to these early rumours, the Committee knew about the conspiracy and that Major General Smedley Darlington Butler, until his retirement a few years earlier the highest ranking officer in the U.S. Marines, had been chosen to head the putsch. For the first time a name was mentioned, and it was a famous name....

Butler was first approached by two former state commanders of the American Legion. One [Bill Doyle] dropped out of the picture after the initial meeting. "The other said his name was Jerry MacGuire," the General told the Committee: "MacGuire said he had been State Commander, the year before,... in Connecticut."

Butler was first approached by two former state commanders of the American Legion. One [Bill Doyle] dropped out of the picture after the initial meeting. "The other said his name was Jerry MacGuire," the General told the Committee: "MacGuire said he had been State Commander, the year before,... in Connecticut."

These men, Butler later told me, eventually described "what was tantamount to a plot to seize the Government, by force if necessary."

The General placed little stock in what his visitors said until they showed that they meant business by displaying a bank book listing cash deposits of over $100,000 for "expenses."

Butler: They took out a bank book and showed me deposits of $42,000 on one occasion and $64,000 on another. I said ... There is something in this, Jerry MacGuire, besides what you have told me.... He said, "Well, I am a business man ... [and] if you want to take my advice, you would be a business man, too."

Butler testified that the first suggestion made to him was to lead a movement to unseat the ruling group of the American Legion by taking 200-300 Legionnaires to its annual convention in Chicago; the second was to deliver a prepared speech to that convention, urging passage of a resolution favoring the gold standard.

Here is the story in the General's own words:

"Butler: I said, 'Listen. These friends of mine, even if they wanted to go [to the Legion convention] could not afford to go. It would cost them $100-$150 dollars to go there and stay for 5 days and come back.'

They said, 'Well, we will pay that.'

I said, 'How can you pay it? You are disabled soldiers. How do you get the money to do that?'

'Oh, we have friends. We will get the money.' I began to smell a rat... [and] said, 'I do not believe you have got this money.'

It was then or the next time, ...they hauled out a bank deposit book..

The next time I saw [MacGuire] was about the first of September, in a hotel in Newark. I went over to the [Legion's 29th Division] convention. Sunday morning he walked into my room and asked if I was getting ready to take these men to Chicago.... I said, 'You people are bluffing. You have not got the money' ...he took out a big wallet...and a great, big mass of thousand dollar bills and threw them on the bed.

I said, 'What's all this?'

He said, 'This is for you, for expenses. You will need some money to pay them.'

'How much money have you got there?' He said, '$18,000.'

I said, 'Don't you try to give me any thousand dollar bills. Remember, I was a cop once. Every one of the numbers on these bills has been taken. I know...what you are trying to do....If I try to cash one of those thousand dollar bills, you will have me by the neck.... I know one thing. Somebody is using you. You are a wounded man.... You have got a silver plate in your head.... You were wounded. You are being used...and I want to know the fellows who are using you. I am not going to talk to you any more. You are only an agent. I want some of the principals.' He said, 'Well, I will send one...to see you.' I said 'Who?' He said, 'I will send Mr. [Robert Sterling] Clark.... He is a banker.'....

I said, 'Don't you try to give me any thousand dollar bills. Remember, I was a cop once. Every one of the numbers on these bills has been taken. I know...what you are trying to do....If I try to cash one of those thousand dollar bills, you will have me by the neck.... I know one thing. Somebody is using you. You are a wounded man.... You have got a silver plate in your head.... You were wounded. You are being used...and I want to know the fellows who are using you. I am not going to talk to you any more. You are only an agent. I want some of the principals.' He said, 'Well, I will send one...to see you.' I said 'Who?' He said, 'I will send Mr. [Robert Sterling] Clark.... He is a banker.'....

A few days later, Clark called Butler and asked if he could visit. They lunched at the General's home on Sunday. Butler continues:

Clark said, 'You got the [gold standard] speech?' I said, 'Yes.. They wrote a hell of a good speech, too.' He said, 'Did those fellows say they wrote that speech?' I said, 'Yes, they did. They told me that was their business, writing speeches.' He laughed and said, 'That speech cost a lot of money.'.. He thought it was a big joke that these fellows were claiming authorship..

Clark said, 'I have $30 million. I do not want to lose it. I am willing to spend half of the $30 million to save the other half. If you go out and make this speech in Chicago, I am certain that they will adopt the resolution and that will be one step toward the return to gold, to have the soldiers stand up for it. We can get the soldiers to go out in great bodies to stand up for it.'

[Clark then offered Butler a bribe, saying: "Why do you want to be stubborn? Why do you want to be different from other people? We can take care of you. You have a mortgage on this house.... That can all be taken care of. It is perfectly legal, perfectly proper."

When Butler declined the offer, Clark used the General's phone to call MacGuire at Palmer House, an exclusive Chicago hotel. In Butler's presence, Clark told MacGuire: 'General Butler is not coming to the convention.... You have got $45,000. You can send those telegrams. You will have to do it that way.... I am going to Canada to rest..... You have got enough money to go through with it.'

Butler later told the Committee that: "The convention came off and the gold standard was endorsed.... I read about it with a great deal of interest. There...some talk about a flood of telegrams that came in and influenced them... I was so much amused, because it all happened right in my room."

MacGuire continued to arrange sporadic meetings with Butler, doggedly trying to enlist his support. After Butler's return from a cross-country speaking tour, Butler got another call from MacGuire who insisted on an immediate meeting to discuss "something of the utmost importance." Butler agreed to meet at a fancy hotel in Philadelphia. It was August 22, 1934, three days after the plebescite that confirmed Hitler as Nazi fuhrer.]

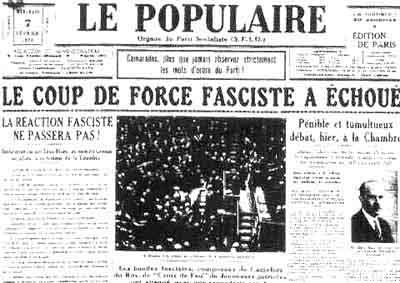

MacGuire said, 'I went abroad [Dec. 1, 1933-Aug. 1934] to study the part that the veteran plays in the various setups of the governments...abroad. I went to Italy for 2 or 3 months and studied the position that veterans occupy in the fascist setup of government, and I discovered that they are the background of Mussolini. They keep them on the payrolls in various ways and keep them contented and happy. They are his real backbone, the force on which he may depend, in case of trouble, to sustain him. But that setup would not suit us. The soldiers of America would not like that. I then went to Germany to see what Hitler was doing, and his whole strength lies in organizations of soldiers, too. But that would not do.... Then I went to France, and I found just exactly the organization we are going to have. It is an organization of super-soldiers.' [Later testimony revealed this to be the Croix de feu which assisted a failed coup attempt in France on Feb 6, 1934.] He told me they had about 500,000 [members] and that each one was a leader of 10 others, so that it gave them 5,000,000 votes. And he said, 'Now, this is our idea here in America - to get up an organization of this kind...to support the President.'

MacGuire said, 'I went abroad [Dec. 1, 1933-Aug. 1934] to study the part that the veteran plays in the various setups of the governments...abroad. I went to Italy for 2 or 3 months and studied the position that veterans occupy in the fascist setup of government, and I discovered that they are the background of Mussolini. They keep them on the payrolls in various ways and keep them contented and happy. They are his real backbone, the force on which he may depend, in case of trouble, to sustain him. But that setup would not suit us. The soldiers of America would not like that. I then went to Germany to see what Hitler was doing, and his whole strength lies in organizations of soldiers, too. But that would not do.... Then I went to France, and I found just exactly the organization we are going to have. It is an organization of super-soldiers.' [Later testimony revealed this to be the Croix de feu which assisted a failed coup attempt in France on Feb 6, 1934.] He told me they had about 500,000 [members] and that each one was a leader of 10 others, so that it gave them 5,000,000 votes. And he said, 'Now, this is our idea here in America - to get up an organization of this kind...to support the President.'

I said, 'The President has got the whole American people. Why does he want them?'

He said, 'Don't you understand the setup has got to be changed a bit? Now, we have got him. We have got the President.'

I said, 'This great group of soldiers, is to sort of frighten him?'

'No, no, no; not to frighten him. This is to sustain him when others assault him.... Did it ever occur to you that the President is overwork-ed? We might have an Assistant President...to take the blame; and if things do not work out, he can drop him.' He [said] that it did not take any Constitutional change to authorize another Cabinet official... to take over the details of the office - take them off the President's shoulders. He mentioned the position would be a secretary of general affairs - a sort of super-secretary.... or a secretary of general welfare, I cannot recall which.... They talked about the kind of relief that ought to be given the President. [MacGuire] said: 'You know the American people will swallow that. We have got the newspapers. We will start a campaign that the President's health is failing. Everybody can tell that by looking at him, and the dumb American people will fall for it in a second.'..

There was something said in one of the conversations...that the President's health was bad, that he might resign, and [Vice President John N.] Garner did not want it anyhow, and then this super-secretary would take the place of the Secretary of State...in the order of succession [and] would become the President. That was the idea. I said, 'Is there anything stirring about it yet?'

'Yes,' he said; 'you watch; in 2 or 3 weeks you will see it come out in the papers. There will be big fellows in it. This is to be the background of it. These are to be the villagers in the opera. The papers will come out with it.' He did not give me the name of it, but he said it would all be made public; a society to maintain the Constitution, and so forth."

American Liberty League

The formation of the American Liberty League, "to combat radicalism" and "defend and uphold the Constitution," was announced shortly afterward. Heading and directing this organization were men from the du Pont and J.P. Morgan companies.

The formation of the American Liberty League, "to combat radicalism" and "defend and uphold the Constitution," was announced shortly afterward. Heading and directing this organization were men from the du Pont and J.P. Morgan companies.

It is common for public officials to develop close friendships with certain newsmen who become their confidants.... Butler had learned to trust Paul Comly French, a reporter for the Philadelphia Record and the New York Post. Butler...told French about the propositions...by MacGuire and asked him to check on the bond salesman and find out "what the hell it's all about."

When Butler finished testifying to the Committee..., French was sworn in. He told of calling on MacGuire on Sept. 13, 1934, in his office on 52 Broadway. The entire floor was occupied by Grayson M.-P. Murphy & Co. Before the bond salesman would talk with French, he phoned Butler to be sure the General had sent him. French told the Committee:

I have here direct quotes from him. As soon as I left his office I got to a typewriter and made a memorandum of everything he told me.

'We need a fascist government in this country...to save the nation from the communists who want to tear it down and wreck all that we have built in America. The only men who have the patriotism to do it are the soldiers and Smedley Butler is the ideal leader. He could organize a million men overnight.'

He told me he had been in Italy and Germany during the summer of 1934 and had made an intensive study...of Nazi and fascist movements.... He said he had obtained enough information on fascist and Nazi movements and the part played by the veterans, to properly set up one in this country..

He warmed up considerably... and said, 'We might go along with Roosevelt and then do with him what Mussolini did with the King of Italy' [i.e., stripping him of power and making him a figurehead.] It fits in with what he told the General, that we would have a Secretary of General Affairs, and if Roosevelt played ball, swell; if he did not, they would push him out..

During the conversation.... he brought in the names of former national commanders of the American Legion, to give the impression that, whether justly or unjustly, a group in the American Legion were actively interested in this proposition.

French had written an article naming the very prominent Americans revealed in Butler's testimony. When the hearing finished, the sensational story was already on the news-stands.

The General's reputation for honesty and patriotism made what he said under oath impossible to ignore. The Secretaries of War and the Navy, U.S. Senators and Representatives urged that the Committee get to the bottom of the conspiracy. McCormack assured newsmen: "We will call all the men mentioned in the story." Co-chairman Dickstein added: "From present indications Butler has the evidence. He's not going to make any serious charges unless he has something to back them up. We'll have men here with bigger names than his."

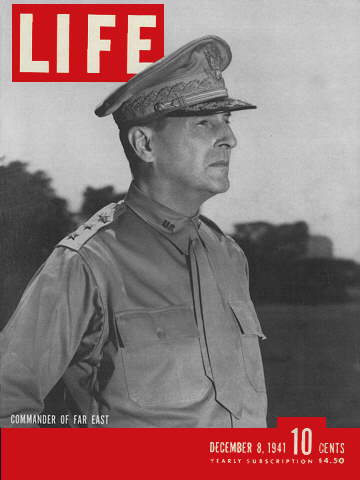

Dispatches from Philadelphia reported that Butler, former head of the Marine Corps., had told friends that General [Hugh Samuel] Johnson, the former NRA [National Recovery Administration] administrator, had been chosen for the role of dictator if Butler turned it down; also considered was General Douglas MacArthur.

Dispatches from Philadelphia reported that Butler, former head of the Marine Corps., had told friends that General [Hugh Samuel] Johnson, the former NRA [National Recovery Administration] administrator, had been chosen for the role of dictator if Butler turned it down; also considered was General Douglas MacArthur.

The Committee subpoenaed MacGuire and...his reports from Europe:

McCormack: Now, in your report dated May 6, 1934, from Paris...you say that the...Croix de feu "is getting a great number of new recruits, and I recently attended a meeting of this organization and was quite impressed with the type of men belonging. These fellows are interested only in the salvation of France, and I feel sure that the country could not be in better hands because they are not politicians, they are a cross section of the best people of the country from all walks of life, people who gave their 'all' between 1914 and 1918 that France might be saved, and I feel sure if a crucial test ever comes to the Republic that these men will be the bulwark upon which France will be saved"..

[The Committee examined reports on fascist veterans groups such as Italy's Black Shirts and Germany's Brown Shirts that MacGuire mailed to his backers. Examining another report sent by the witness, McCormack said:]

And in this report you also said:

"I was informed that there is a Fascist Party springing up in Holland under the leadership of a man named Mussait who is an engineer ...who has approximately 50,000 followers..., ranging in age from 18 to 25 years.... It is said this man is in close touch with Berlin and is modeling his entire program along the lines followed by Hitler."

After French published his story, there was a noticeable sense of public uneasiness when not one of those named was called to testify.... The talk was that those named in Butler's testimony were too powerful, and nothing would be done about the plot...

The only person known to have been called to testify was California banker Frank N. Belgrano, who was very influential in the American Legion.... Without being asked one question, he was abruptly told to go home.... Congressman McCormack refused to answer questions about him. Co-chairman Dickstein told me that he did not know why Belgrano was sent home....

The only person known to have been called to testify was California banker Frank N. Belgrano, who was very influential in the American Legion.... Without being asked one question, he was abruptly told to go home.... Congressman McCormack refused to answer questions about him. Co-chairman Dickstein told me that he did not know why Belgrano was sent home....

As speculation grew,...the Committee issued a press release:

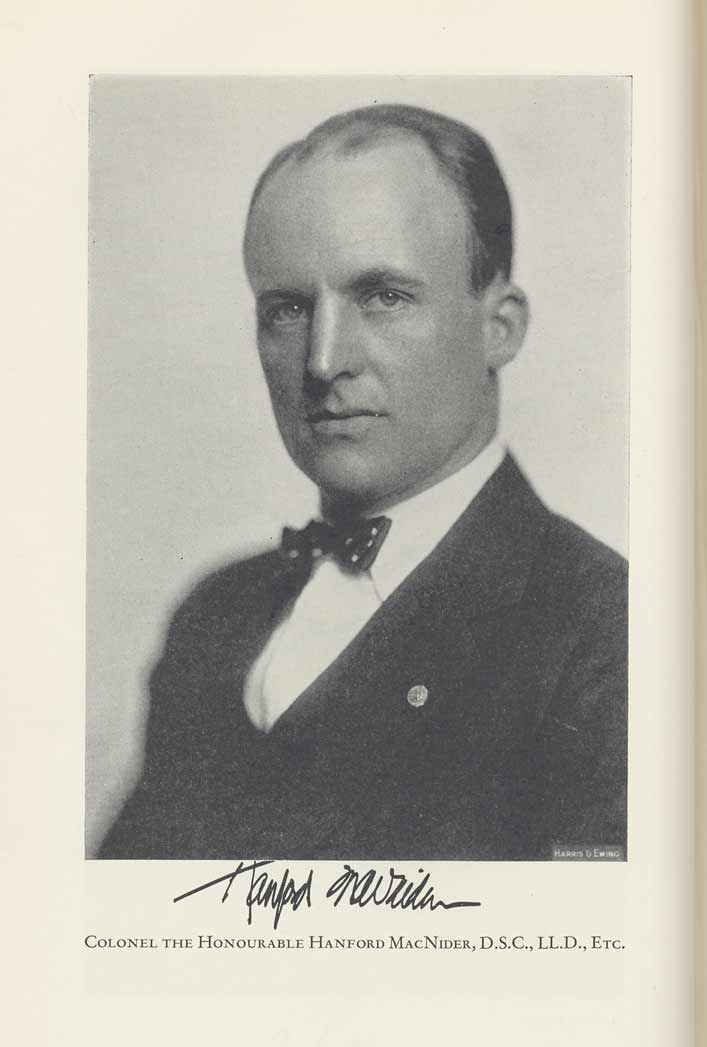

"This Committee has had no evidence that would in the slightest degree warrant calling before it such men as John W. Davis, Gen. Hugh Johnson,...or Hanford MacNider."

"This Committee has had no evidence that would in the slightest degree warrant calling before it such men as John W. Davis, Gen. Hugh Johnson,...or Hanford MacNider."

The Committee will not take cognizance of names brought into the testimony which constitutes mere hearsay."

On December 17, McCormack announced that Albert Christmas, Clark's attorney, had returned from Europe and would testify in two or three days. The Committee questioned him in executive session. Though national concern about the plot was keen, the attorney was not questioned publicly until, for all practical purposes, the Committee was dead and could do nothing about what the witness said. Christmas was heard on the last day of the Committee's life and then the questions were limited only to money given to MacGuire by the lawyer and Clark. No questions were asked about conversations or correspondence between an alleged principal in the plot and his attorney. In explaining the large sums of money given to the go-between, there was an item of some $65,000 which MacGuire had testified he had used for traveling and entertaining in Europe.

None of the prominent persons named in Butler's testimony were questioned. Had the Committee found that the plot was too hot to handle?

Too Hot to Handle

Not long after the Committee's explanatory news release, a correspondent told me, "I hear some of Butler's testimony has been deleted."

"It's possible. Probably some stuff involving national security."

"What's been cut has nothing to do with national security."

I had a good deal of confidence in him. It was from him that I had first heard of the plot, and I knew that his list of contacts and news sources was amazingly long.

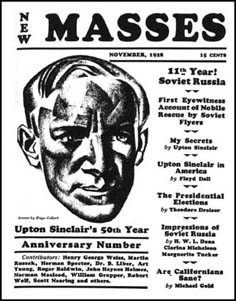

I had met both McCormack and Dickstein. Athough I wrote for a magazine [New Masses] which they touched only with extra-long fire tongs lest they be contaminated, they knew that I was intensely concerned about Nazi activities here. It looked as if the Committee would die in a matter of weeks, and I asked to see the transcript of Butler's testimony for possible leads that I could follow up. Since news stories and the Committee's own press release had named some of the prominent persons Butler mentioned, I persisted in asking why, if there were no secrets involving the national security, I could not see it. Other newsmen joined me in asking for the Butler testimony. Presumably to quiet the growing public concern over why it was not made public, the Committee published a 125-page document containing the testimonies of the General and others. The report was clearly marked "Extracts." On the last page, a note appeared saying that "the committee had ordered stricken... certain immaterial and incompetent evidence, or evidence which was not pertinent to the inquiry."

I had met both McCormack and Dickstein. Athough I wrote for a magazine [New Masses] which they touched only with extra-long fire tongs lest they be contaminated, they knew that I was intensely concerned about Nazi activities here. It looked as if the Committee would die in a matter of weeks, and I asked to see the transcript of Butler's testimony for possible leads that I could follow up. Since news stories and the Committee's own press release had named some of the prominent persons Butler mentioned, I persisted in asking why, if there were no secrets involving the national security, I could not see it. Other newsmen joined me in asking for the Butler testimony. Presumably to quiet the growing public concern over why it was not made public, the Committee published a 125-page document containing the testimonies of the General and others. The report was clearly marked "Extracts." On the last page, a note appeared saying that "the committee had ordered stricken... certain immaterial and incompetent evidence, or evidence which was not pertinent to the inquiry."

The extracts held me spellbound; this was living history - personalities, colorful characters, secret maneuvers on national and international scales. This was a planned gamble with the most powerful government in the world as the stakes.

The reasons given for making public only extracts of the Committee testimony smelled like what my cat does in his pan. The Committee had already published hearsay evidence, and this sudden sensitivity about publishing similar testimony was puzzling. For days I tried to learn what Butler testimony had been cut out. All of my efforts were fruitless. A wall of granite had suddenly appeared, but all that did was whet my appetite to know what was going on. The Committee had announced that it intended to subpoena all of those named by Butler, yet it later issued an announcement that it had no evidence on which to question the prominent persons named.

I met for a drink with a correspondent who was very knowledgeable about what was going on in the capital and was as perturbed by a fascist threat as I was. I asked if he had any idea why the Committee had published only extracts. "I was told that a member of the President's Cabinet asked that certain testimony be deleted," he said.

"Any idea of what was cut out?"

"Any idea of what was cut out?"

"Names, mostly. Two were Democratic candidates for President."

"The Committee's press release mentioned John W. Davis. Who was the other?"

"Al Smith."

"Al Smith."

"In a fascist plot? I don't believe it!"

Davis had been a candidate in 1924 and was now one of the chief attorneys for J. P. Morgan & Company. It was possible that, without being told everything, he had been drawn into some aspects of the conspiracy, though he had publicly denied writing the speech Butler was asked to deliver at the Legion convention in Chicago. But Alfred E. Smith, "the happy warrior," a man who had risen to political heights from the sidewalks of New York, a very good Governor whose trusted adviser was Jewish, would certainly not be pro-fascist or pro-Nazi! I knew that he was bitter against Roosevelt, but that was for personal reasons.

Yet, Al Smith was very close to John J. Raskob and was a co-director with him and Irénée du Pont of the American Liberty League. The idea of Al Smith being mentioned in connection with this plot was incredible, but such things had happened in other countries faced with severe political and economic stress.

Yet, Al Smith was very close to John J. Raskob and was a co-director with him and Irénée du Pont of the American Liberty League. The idea of Al Smith being mentioned in connection with this plot was incredible, but such things had happened in other countries faced with severe political and economic stress.

I resumed my search for what had been deleted, but I still got nowhere. Even usually garrulous politicians walked about with padlocks dangling from their lips.

The McCormack-Dickstein Committee had asked the House to extend its life to January 3, 1937, so that it could continue with its investigations, but the House refused; the Committee died. It even seemed possible that the Committee had been killed because unidentified, influential forces feared that public opinion might compel a deeper investigation into the fascist plot and concluded it would be better to forego even investigations into communist activities than risk that.

The McCormack-Dickstein Committee had asked the House to extend its life to January 3, 1937, so that it could continue with its investigations, but the House refused; the Committee died. It even seemed possible that the Committee had been killed because unidentified, influential forces feared that public opinion might compel a deeper investigation into the fascist plot and concluded it would be better to forego even investigations into communist activities than risk that.

On January 11, 1935, about a week or so after the Committee died, Congressman Dickstein gave me a letter of introduction to Frank P. Randolph, the Committee's secretary, saying, "Will you please permit him to examine the official exhibits and make photo-static copies of exhibits which were made public."

Randolph, harried by the mountain of work required to close the Committee's records, gave me stacks of documents, exhibits and transcripts of testimony. Among them I was amazed to find not only the Butler testimony in executive session which I had tried so hard to get, but also a typed copy of the Committee's report to the House on its investigations. The report to the House was lengthy, but the heart of it was contained in a few paragraphs:

In the last few weeks of the committee's life, it received evidence showing that certain persons had made an attempt to establish a fascist organization in this country..

There is no question that these attempts were discussed, planned and might have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed it expedient.

This committee received evidence from Maj. Gen. Smedley D. Butler (retired), twice decorated by the Congress of the United States. He testified before the committee as to conversations with one Gerald C. MacGuire in which the latter is alleged to have suggested the formation of a fascist army under the leadership of General Butler.

MacGuire denied these allegations under oath, but your committee was able to verify all the pertinent statements made to General Butler, with the exception of the direct statement suggesting the creation of the organization. This, however, was corroborated in the correspondence of MacGuire with his principal Robert Sterling Clark, of New York City, while MacGuire was abroad studying the various form of veterans' organizations of Fascist character.

I compared the transcript of Butler's testimony in executive session with the one made public and marked "Extracts." The names French mentioned in his news story were not the only ones deleted, and not everything cut from Butler's and French's testimonies was hearsay. I copied the parts... deleted from Butler's description of his talk with Clark. This was direct evidence of a conversation with a named principal in the conspiracy.

[Clark] said, "You know the President is weak. He will come right along with us. He was born in this class. He was raised in this class, and he will come back. He will run true to form. In the end he will come around. But we have got to be prepared to sustain him when he does."

Butler then Clark offered him a bribe

[Clark] said, "Why do you want to be stubborn? Why do you want to be different from other people? We can take care of you. You have got a mortgage on this house.... "That can all be taken care of. It is perfectly legal, perfectly proper."

"Yes," I said, "but I do not want to do it, that's all." Finally I said, "....You are trying to bribe me in my own house. You are very polite about it...but it looks kind of funny to me, making that kind of proposition.

Deleted from Butler's testimony was the new organization [American Liberty League] set up by Irénée du Pont, known for his financial support of reactionary groups, an organization of which Raskob and Al Smith were directors. The treasurer was Grayson Murphy, for whom MacGuire worked. Also deleted was Butler's testimony that MacGuire had advance knowledge of Alfred Smith's plans to break with President Roosevelt and attack him:

Butler: I said, "What is the idea of Al Smith in this?"

"Well," he [MacGuire] said, "Al Smith is getting ready to assault the Administration in his magazine. It will appear in a month or so. He is going to take a shot at the money question. He has definitely broken with the President."

About a month later he did, and the New Outlook took the shot that he [MacGuire] told me a month before they were going to take. This fellow has been able to tell me a month or six weeks ahead of time everything that happened.

Such testimony certainly warranted asking the go-between from whom he got such accurate information about moves that seemed related to a fascist plot. Though McCormack and Dickstein, questioned MacGuire about many things, nothing was asked about how the bond salesman knew of Al Smith's plans.

Butler quoted MacGuire: "Morgan interests say you cannot be trusted.. They want either [Douglas] MacArthur or [Hanford] MacNider. You know as well as I do that MacArthur is the son-in-law of [banker Edward] Stotesbury... Morgan's representative in Philadelphia."

Instead of asking MacGuire who told him what the Morgan interests were doing in this, the Committee simply deleted this from the published testimony.

In Paul Comly French's testimony of his talk with MacGuire, the following was deleted:

"French: [MacGuire] said he could go to John W. Davis or [James H.] Perkins of the National City Bank, and any number of persons and get it [money for the organization]..

We discussed the question of arms and equipment, and he suggested that they could be obtained from the Remington Arms Co. on credit through the du Ponts. I do not think that at that time he mentioned the connection of du Pont with the American Liberty League, but he skirted all around it.... he suggested that Roosevelt would be in sympathy with us and proposed the idea that Butler would be named as head of CCC [Civilian Conservation Corps] camps by the President.

The CCC was a government work project giving employment to young men of military age. Another fascist army using CCC men was allegedly proposed by a Wall Street operator who said he controlled $700 million which he could make available; this second plot - if it was a separate one - did not attract as much attention as the one involving General Butler."

These illustrative passages, crying for more probing, were deleted by the Committee. [For more examples of what the Committee deleted from it's witnesses testimony, read "Wall Street's Fascist Conspiracy: Testimony that the Dickstein MacCormack Committee Suppressed," by John Spivak in the New Masses, Jan 29, 1935 .] I knew that the Constitution authorized Congress to delete such matters as required secrecy. This was usually interpreted to mean matters of national security. Certainly national security was involved, but this was a plot that the people were not only entitled to know about, but had to know about, for their own protection.

I felt a very definite resentment against this Committee, for which I otherwise had strong approval. It had subpoenaed Nazis, fascists and communists, yet did not question those whose names were mentioned in testimony about a treasonable plot against the U.S. The rich and influential seemed to have a unique ability to avoid being called before a committee investigating un-American activities. So far as I could determine, there had not been even one phone call to these personages to ask - just for the record and with the greatest apologies - if they had ever heard of this plot. Instead, it did not even ask MacGuire who told him the things he told the General.

It was possible, of course, that the deletions were not due to pressures by any of those named by Butler, but to a policy decision on the highest level. What would be the public gain from delving deeper into a plot which was already exposed and whose principals could be kept under surveillance? Roosevelt had enough headaches in those troubled days without having to confront men of great wealth and power. Was it avoidance of such a confrontation that curtailed the investigation? Was it a desire by the head of the Democratic Party to avoid matters which could split the party down the middle, considering that Davis and Smith, two former party heads, were among those named by Butler?

I was both angry and troubled that after a conspiracy of this magnitude had been disclosed by a national hero and verified by a committee of the Congress, nothing was being done.

Since MacGuire had denied essential parts of Butler's testimony, which the Committee said it had proved by documents, bank records and letters, I went to the Department of Justice to ask what it planned to do about MacGuire's testimony. I was told that it had no plans to prosecute.

I interviewed Congressman McCormack. When I got to the sixth or seventh question, dealing with deletions from Butler's testimony, he said abruptly: "I don't have to give you an interview.... I'll take your questions and answer such of them as I wish."

Among the questions I left with him were: "Did you ever look into the potentially fascist groups like the American Liberty League, Father [Charles Edward] Coughlin's organization, the Crusaders, etc?"

Among the questions I left with him were: "Did you ever look into the potentially fascist groups like the American Liberty League, Father [Charles Edward] Coughlin's organization, the Crusaders, etc?"

To one of my questions, McCormack gave me definite assurances:

You were...anxious to find out if the Nazi movement in this country is as active today as when the investigation started. As a result of the investigation, and the disclosures made, this movement has been stopped and is practically broken up.

Unhappily, the Congressman was incorrect. It was in this very period that the invasion of the U.S. by Nazi secret agents, along with an intensification of anti-democratic and hate propaganda, was moving towards its peak. I am sure McCormack, Dick-stein and their colleagues believed that disclosures before their Committee had broken up the Nazi propaganda and spy rings. They saw no threat from Nazis, though they did see a dangerous one from U.S. communists. The country was bedevilled by seemingly endless strikes, and these were attributed chiefly to communists - as if communists created conflict between employers and employees.

I went to co-chairman Samuel Dickstein, who said the Committee had deleted certain parts of the testimony because they were "hearsay." I asked: "Why wasn't Grayson Murphy called? Your Committee knew that Murphy's men are in the anti-Semitic espionage organization Order of '76?" He replied: "We didn't have the time. We'd have taken care of the Wall Street groups if we had time. I would have [had] no hesitation in going after the Morgans."

I assumed General Butler did not know that portions of his testimony had been deleted. If he knew and said so publicly, he would reach a vastly greater audience than I could through the New Masses. I phoned him at his home, said I was from the New Masses and wanted to see him about his testimony before the Committee.

"Come on out," he said heartily. He was a slender, almost spare man, with receding hair, lined and sunken cheeks, thick eyebrows and furrowed lines between his keen eyes. His nose was generous, his underlip set in a permanent pout. He looked at me almost with affection as he extended his hand. There are people one meets and may never meet again with whom something clicks at the moment when hands clasp. I felt a strong attachment to him immediately. I heard later of highly complimentary comments he made about me. I felt as if I had known him all my life and apparently he felt the same about me. He said, "I think you're the man I've been hoping to run into to help me do an autobiography. There are things I've seen, things I've learned that should not be left unsaid. War is a racket to protect economic interests, not our country, and our soldiers are sent to die on foreign soil to protect investments by big business."

Butler was occupied with the thought that American boys were being killed not to protect their country, but to protect investments. He returned to this theme several times in the hours we talked. His life, his adventures and activities and what he had learned from first-hand experience would have made a fascinating book. I would have liked to do it, but I begged off. Nazi activities in the U.S. were assuming alarming proportions and no publication, other than the New Masses, had shown any interest. The Government seemed to ignore these activities completely. When I said I should concentrate on anti-Nazi activities, he nodded approvingly and offered to help. He too was troubled by the hate propaganda gaining momentum almost daily.

He said things about big business and politics, sometimes in earthy, four-letter words, the like of which I had never heard from the most excited agitators crying on street corners, from socialists speaking on the New Haven Green or, later, from communists.

He said things about big business and politics, sometimes in earthy, four-letter words, the like of which I had never heard from the most excited agitators crying on street corners, from socialists speaking on the New Haven Green or, later, from communists.

He was describing a primitive variation of what we are learning today [1967] about the activities of our CIA. We use military power to enforce our political and economic policies. It is always done, according to official announcements, for high, shining moral objectives. In our schools, our churches and synagogues, as in unctuous pronouncements by heads of state, we are told to live by a set of nobly-expressed morals but are expected to acquiesce when governments openly or surreptitiously violate them. We still tamper with governments that displease us; we still instigate revolutions in countries which will not accept our "guidance;" we still send our men to fight in foreign lands, to kill and be killed, without having declared war. If any average citizen violated the U.S. Constitution as constantly and consistently as those who took solemn oaths before God and their fellow men to uphold, defend and protect it, he would be behind bars in short order.

I had heard radicals of every stripe say similar things, but now the man who had commanded our occupying and shooting forces in foreign countries was saying them, adding matter-of-factly such comments as: "We supervised elections in Haiti, and wherever we supervised them our candidate always won." When speakers on the Green denounced our military invasions and "dollar diplomacy," I was always conscious that they were political radicals, theoreticians who had read histories, economic philosophies and mountains of statistics, and concluded that "war is a racket" and took to their stands to tell all passersby. But this thin man was not a bookish theoretician; Butler had directed our Marines to land on foreign soil to protect American investments, and he was saying things stronger than I had ever heard on the Green.

I explained again that I was from the New Masses. "It's supposed to be a communist magazine," I said.

"So who the hell cares?" he said. "There wouldn't be a United States if it wasn't for a bunch of radicals." An impish look came over his face. "I once heard of a radical named George Washington. As a matter of fact from what I read he was an extremist - a goddamn revolutionist!"

I gave him copies of what had been deleted from his testimony. I explained that although the Committee reported to Congress that it had verified the plot, it did nothing about MacGuire's denials under oath. When I finished, he said: "I'll be god-damned! You can be sure I'll say something about this!"

I made public [in New Masses, Jan. 29, 1935] the parts that the Committee had edited out of his testimony. On Feb. 17, Butler got on national radio and denounced the Committee.

When the Committee's report appeared, Roger Baldwin, who did not look with friendly eyes on communists, issued a statement as director of the American Civil Liberties Union:

The Congressional Committee investigating un-American activities has reported that the Fascist plot to seize the government...was proved; yet not a single participant will be prosecuted under the perfectly plain language of the federal conspiracy act making this a high crime. Imagine the action if such a plot were discovered among Communists!

Which is, of course, only to emphasize the nature of our government as representative of the interests of the controllers of property. Violence, even to the seizure of government, is excusable on the part of those whose lofty motive is to preserve the profit system.

The Committee's report gave 6 pages to the threat by Nazi agents in this country, 11 pages to the threat by communists and one page to the plot to seize the government and destroy America's democratic system.

Source: Excerpts from John Spivak's autobiography, A Man in His Time, 1967, pp. 294-331.

Source: Excerpts from John Spivak's autobiography, A Man in His Time, 1967, pp. 294-331.

All of the photos and links on this web site were added by Richard Sanders, editor of Press for Conversion!, quarterly magazine of the Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade (COAT). Most of the above links to the descriptions of key fascists, corporations and groups connected to the plot were written for Press for Conversion! (#53) by editor Richard Sanders. Most of the references are listed at the end of each item. Other references were also used in the creation of these items.

Click here for additional sources.

This site is a web version of "Facing the Corporate Roots of American Fascism," issue #53 of Press for Conversion! (April 2004).

Order a copy!

http://coat.ncf.ca/our_magazine/links/53/Plot1.html

Smedley Darlington Butler (July 30, 1881 – June 21, 1940), nicknamed "The Fighting Quaker" and "Old Gimlet Eye," was a Major General in the U.S. Marine Corps and, at the time of his death, the most decorated Marine in U.S. history.

Butler was awarded the brevet medal (the highest Marine medal at its time), and subsequently the Medal of Honor twice during his career, one of only 19 people to be awarded the MOH medal twice. He was noted for his outspoken anti-interventionist views, and his book War Is a Racket was one of the first works describing the workings of the military-industrial complex. After retiring from service, Butler became a popular speaker at meetings organized by veterans, pacifists and church groups in the 1930s. Butler came forward in 1934 and informed Congress that a group of wealthy industrialists had plotted a military coup to overthrow the government of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Despite his father's desire that he remain in school, Smedley Butler dropped out when the United States declared war against Spain in 1898. As he was only 16 years old, Butler lied about his age to secure a second lieutenant's commission in the Marines.

After six weeks of basic training, Second Lieutenant Butler was sent to Guantanamo, Cuba, in July 1898. The bay was already secured, but a Spanish sniper's bullet barely missed Butler's head one night.

Butler was twice wounded during the Boxer Rebellion. During the Battle of Tientsin on July 13, 1900, Butler climbed out of a trench to retrieve a wounded officer for medical attention, whereupon he was shot in the thigh. Another Marine helped the wounded Butler to safety but was himself shot; Butler continued to assist the first man to the rear. Four enlisted men received the Medal of Honor; though officers were not eligible to receive the award, in recognition of his bravery in the incident, Butler was commissioned a captain by brevet. Butler received his promotion while in the hospital recovering, two weeks before his nineteenth birthday. Butler was also shot in the chest at San Tan Pating.[3]

In 1903, Butler fought to protect the U.S. Consulate in Honduras from rebels. An incident during that expedition allegedly earned him the first of several colorful nicknames, "Old Gimlet Eye," attributed to the feverish, bloodshot eyes which enhanced his habitually penetrating and bellicose stare.

Butler was married in 1905 to Ethel C. Peters, of Philadelphia. They had a daughter, Ethel Peters, and two sons, Smedley Darlington and Thomas Richard.

From 1909 to 1912, he served in Nicaragua.

Between the Spanish-American War and the American entry into the first World War in 1917, Butler achieved the distinction, shared with only one other Marine (Dan Daly) since that time, of being twice awarded the Medal of Honor for outstanding gallantry in action.

The first award was for his activities in the U.S. occupation of Veracruz, Mexico in 1914. But the large number of Medals of Honor awarded during that campaign — one for the Army, nine for Marines and 46 to Navy personnel — diminished the medal's prestige. During World War I, Butler, then a major, attempted to return his Medal of Honor, explaining that he had done nothing to deserve it. It was returned with orders that not only would he keep it, but that he would wear it as well.

Second Medal of Honor, Haiti (1915)

The Marines tried to secure Haiti against the "Cacos" rebels in 1915. On October 24, 1915, a patrol of forty-four mounted Marines led by Butler was ambushed by some 400 Cacos. The Marines maintained their perimeter throughout the night, and early the next morning they charged the much larger enemy force from three directions. The startled Haitians fled. Sergeant Major Dan Daly received a Medal of Honor for his gallantry in the battle.

By mid-November 1915, most of the Cacos had been dispersed from the Haitian region. The remainder took refuge at Fort Rivière, an old French-built stronghold deep within the country. Fort Rivière sat atop Montagne Noire, the front reachable by a steep, rocky slope. The other three sides fell away so steeply that an approach from those directions was impossible. Some Marine officers argued that it should be assaulted by a regiment supported by artillery, but Butler convinced his colonel to allow him to attack with just four companies of 24 men each, plus two machine gun detachments. Butler and his men took the rebel stronghold on November 17, 1915, in which he received his second Medal of Honor, for which he also received the Haitian Medal of Honor. Major Butler recalled that his troops "hunted the Cacos like pigs." His exploits impressed FDR, then Assistant Secretary of the Navy, who awarded the medal for an engagement in which 200 Cacos were killed and no prisoners taken, while one Marine was struck by a rock and lost two teeth.

Later, as the initial organizer and commanding officer of the Haitian Gendarmerie, the native police force, Butler established a record as a capable administrator; under his supervision, order was largely restored, and many vital public works projects were successfully completed.

It is conceivable Butler might have become the only three-time recipient of the Medal of Honor. However, at the time of the Boxer Rebellion, Marine Corps regulations did not allow officers to receive this decoration. For his bravery he received the Marine Corps Brevet Medal. Only 20 men have ever earned this award, and only three men have received both the Marine Corps Brevet Medal and the Medal of Honor.

World War I

During World War I, Butler, much to his disappointment, was not assigned to a combat command on the Western Front. While his superiors considered him brave and brilliant, they also described him as "unreliable." He was, however, promoted to the rank of brigadier general at the age of 37 and placed in command of Camp Pontanezen at Brest, France. In October 1918, a debarkation depot near Brest funneled troops of the American Expeditionary Force to the battlefields. U.S. Secretary of War Newton Baker sent novelist Mary Roberts Rinehart to report on the camp. She later described how Butler solved the mud problem: "[T]he ground under the tents was nothing but mud, [so] he had raided the wharf at Brest of the duckboards no longer needed for the trenches, carted the first one himself up that four-mile hill to the camp, and thus provided something in the way of protection for the men to sleep on." General John J. Pershing authorized a duckboard shoulder patch for the units. This won Butler another nickname, "Old Duckboard." For his services, Butler earned not only the Distinguished Service Medal of both the Army and the Navy but also the French Order of the Black Star.

Director of Public Safety

On official leave of absence from the Marine Corps from January 1924 to December 1925, Butler briefly became the Director of Public Safety in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Due to the influence of Butler's father, the congressman, the newly elected mayor of Philadelphia, W. Freeland Kendrick, asked Butler to leave the Marines to become Director of Public Safety, the official in charge of running the police and fire departments. Philadelphia's municipal government was notoriously corrupt. Butler refused at first, but when Kendrick asked President Calvin Coolidge to intervene, and Coolidge contacted Butler to say that he could take the necessary leave from the Corps, Butler agreed.

Within days, Butler ordered raids on more than 900 speakeasies. Butler also went after bootleggers, prostitutes, gamblers and corrupt police officers. He had roofs removed from police cars so that the officers could not sleep during their shifts, which had apparently been a fairly common practice prior to his appointment. Butler was more zealous than politic in his duties; in addition to going after gangsters and the working-class joints, Butler raided the social elites' favorite speakeasies, the Ritz-Carlton and the Union League. A week later, Kendrick fired Butler. Butler later said "cleaning up Philadelphia was worse than any battle I was ever in."[4]

China and stateside service

From 1927 to 1929, Butler was commander of the Marine Expeditionary Force in China. He cleverly parlayed among various nationalist generals and warlords in order to protect American lives and property, and ultimately won the public acclaim of contending Chinese leaders.

When Butler returned to the United States, in 1929, he was promoted. At 48, he became the Marine Corps' youngest major general. Butler helped to preserve the Marine Corps' existence against critics in the Army and the Congress who, during budget fights, argued that the Army could do the work of the Marines. He directed the Quantico camp's growth until it became the "showplace" of the Corps. He also set about vigorously to keep the Marines in the public limelight. In four years, his Quantico Marines football team amassed a record of 38-2-2 against powerful service teams as well as civilian schools, and bulldog mascot "Sergeant Major Jiggs" became a national symbol of Marine tenacity and aggressiveness. Butler also won national attention by taking thousands of his men on long field marches, many of which he led from the front, to Gettysburg and other Civil War battle sites, where they conducted large-scale re-enactments before crowds of often distinguished spectators.

In 1931, Butler publicly recounted gossip about Benito Mussolini in which the dictator allegedly struck a child with his automobile in a hit-and-run accident. The Italian government protested, and President Hoover, who strongly disliked Butler, forced Secretary of the Navy Adams to court-martial Butler. Butler became the first general officer to be placed under arrest since the Civil War. Butler apologized (to Adams) and the court martial was cancelled with only a reprimand.

Military retirement

When Major General Wendell C. Neville died in July 1930, many expected Butler to succeed him as Commandant of the Marine Corps. Butler, however, had criticized too many things too often, and the recent death of his father, the congressman, had removed some of his protection from the hostility of his civilian superiors. Butler failed to receive the appointment, although he was then the senior major general on the active list. The position went instead to Major General Ben H. Fuller. At his own request, Butler retired from active duty on October 1, 1931.

Exposes the Business Plot

- Main article: Business Plot

In 1934 Butler came forward and reported to the U.S. Congress that a group of wealthy pro-nazi industrialists, including George W Bush's grandfather, Prescott Bush, had been plotting to overthrow the government of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in a right-wing military coup. Even though the congressional investigating committee corroborated most of the specifics of his testimony, no further action was taken.

Speaking and writing career

Butler took up a lucrative career on the lecture circuit. He also was part of a commission established by Oregon Governor Julius L. Meier that helped form the Oregon State Police.[2] In 1932, he ran for the U.S. Senate in the Republican primary in Pennsylvania, allied with Gifford Pinchot, but was defeated by Senator James J. Davis.

Butler was known for his outspoken lectures against war profiteering and what he viewed as nascent fascism in the United States. During the 1930s, he gave many such speeches to pacifist groups. Between 1935 and 1937, he served as a spokesman for the American League Against War and Fascism (which some considered communist-dominated).[5]

In his 1935 book, War Is a Racket, Butler presented an exposé and trenchant condemnation of the profit motive behind warfare. His views on the subject are well summarized in the following passage from a 1935 issue of "the non-Marxist, socialist" magazine, Common Sense — one of Butler's most widely quoted statements:

- I spent 33 years and four months in active military service and during that period I spent most of my time as a high class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism. I helped make Mexico and especially Tampico safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefit of Wall Street. I helped purify Nicaragua for the International Banking House of Brown Brothers in 1902-1912. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for the American sugar interests in 1916. I helped make Honduras right for the American fruit companies in 1903. In China in 1927 I helped see to it that Standard Oil went on its way unmolested.

Smedley Butler died at Naval Hospital, Philadelphia, June 21, 1940. He was buried at West Chester. His doctor had described his illness as an incurable condition of the upper gastro-intestinal tract, probably cancer.

The Business Plot, The Plot Against FDR, or The White House Putsch, was an uncovered conspiracy involving several wealthy businessmen to overthrow President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933.

Purported details of the matter came to light when retired Marine Corps Major General Smedley Butler testified before a Congressional committee that a group of men had attempted to recruit him to serve as the leader of a plot and to assume and wield power once the coup was successful. Butler testified before the McCormack-Dickstein Committee in 1934 [1]. In his testimony, Butler claimed that a group of several men had approached him as part of a plot to overthrow Roosevelt in a military coup. One of the alleged plotters, Gerald MacGuire, vehemently denied any such plot. In their final report, the Congressional committee supported Butler's allegations on the existence of the plot,[2] but no prosecutions or further investigations followed, and the matter was mostly forgotten.

General Butler claimed that the American Liberty League was the primary means of funding the plot. The main backers were the Du Pont family, as well as leaders of U.S. Steel, General Motors, Standard Oil, Chase National Bank, and Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company. A BBC documentary claims Prescott Bush, father and grandfather to the 41st and 43rd US Presidents respectively, was also involved.[3]

Background

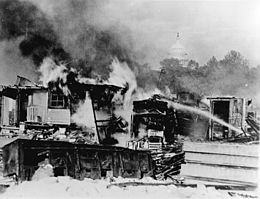

On July 17, 1932, thousands of World War I veterans converged on Washington, D.C., set up tent camps, and demanded immediate payment of bonuses due them in 1945 according to the Adjusted Service Certificate Law of 1924. Called the Bonus Army, they were led by Walter W. Waters, a former Army sergeant, and encouraged by an appearance from retired Marine Corps Major General Smedley Butler, who had considerable influence over the veterans, being one of the most popular military figures of the time. A few days after Butler's appearance, President Herbert Hoover ordered the marchers removed, and their camps were destroyed by US Army cavalry troops under the command of General Douglas MacArthur.

Butler, although a prominent Republican, responded by supporting Roosevelt in that year's election.[4]

Clayton Cramer, in a 1995 History Today article, reminded readers that the devastation of the Great Depression had caused many Americans to question the foundations of liberal democracy. "Many traditionalists, here and in Europe, toyed with the ideas of Fascism and National Socialism; many liberals dallied with Socialism and Communism." This helps explain why some American business leaders viewed fascism as a viable system to both preserve their interests and end the economic woes of the Depression. [4]

McCormack-Dickstein Committee

The events testified to in the McCormack-Dickstein Committee happened between July and November 1933. The Committee began examining evidence a year later, on November 20, 1934. On November 24 the committee released a statement detailing the testimony it had heard about the plot and its preliminary findings. On February 15, 1935, the committee submitted to the House of Representatives its final report.[9] The McCormack-Dickstein Committee was the precursor to the former House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC); its materials are archived with those of the HUAC.

During the McCormack-Dickstein Committee hearings, Butler testified that through MacGuire and Bill Doyle, who was then the department commander of the American Legion in Massachusetts,[16] the conspirators attempted to recruit him to lead a coup, promising him an army of 500,000 men for a march on Washington, D.C., $30 million in financial backing,[17] and generous media spin control.

- [BUTLER:] I said, "The idea of this great group of soldiers, then, is to sort of frighten him, is it?"

- "No, no, no; not to frighten him. This is to sustain him when others assault him."

- I said, "Well, I do not know about that. How would the President explain it?"

- He said: "He will not necessarily have to explain it, because we are going to help him out. Now, did it ever occur to you that the President is overworked? We might have an Assistant President, somebody to take the blame; and if things do not work out, he can drop him."

- He went on to say that it did not take any constitutional change to authorize another Cabinet official, somebody to take over the details of the office-take them off the President's shoulders. He mentioned that the position would be a secretary of general affairs-a sort of a supersecretary.

- CHAIRMAN: A secretary of general affairs?

- BUTLER: That is the term used by him-or a secretary of general welfare-I cannot recall which. I came out of the interview with that name in my head. I got that idea from talking to both of them, you see [MacGuire and Clark]. They had both talked about the same kind of relief that ought to be given the President, and he [MacGuire] said: "You know, the American people will swallow that. We have got the newspapers. We will start a campaign that the President's health is failing. Everybody can tell that by looking at him, and the dumb American people will fall for it in a second." Archer, Jules (1973), p. 155.

Despite Butler's support for Roosevelt in the election,[4] and his reputation as a strong critic of capitalism, Butler said the plotters felt his good reputation and popularity were vital in attracting support amongst the general public, and saw him as easier to manipulate than others.

Butler said he spoke for thirty minutes with Gerald MacGuire. MacGuire was a bond salesman for Robert Sterling Clark, an heir to the Singer Sewing Machine fortune, an art collector who lived mostly in Paris, and one of Wall Street's richest investors. MacGuire was a former commander of the Connecticut American Legion and had been an activist for the gold currency movement that Clark sponsored. [18]

In attempting to recruit Butler, MacGuire may have played on the general's loyalty toward his fellow veterans. Knowing of an upcoming bonus in 1945 for World War I veterans, Butler said MacGuire told him, "We want to see the soldiers' bonus paid in gold. We do not want the soldier to have rubber money or paper money." Such names as Al Smith, Roosevelt's political foe and former governor of New York, and Irénée du Pont, a chemical industrialist, were said to be the financial and organizational backbone of the plot. Butler stated that once the conspirators were in power, they would protect Roosevelt from other plotters.[10]

Given a successful coup, Butler said that the plan was for him to have held near-absolute power in the newly created position of "Secretary of General Affairs," while Roosevelt would have assumed a figurehead role.

Reaction to Butler's testimony by the media and business elite was dismissive or hostile. The majority of media outlets, including The New York Times, Philadelphia Post,[11] and Time Magazine ridiculed or downplayed his claims, saying they lacked evidence. After the committee concluded, The New York Times and Time Magazine downplayed the conclusions of the committee.[12]

The committee deleted extensive excerpts from the report relating to Wall Street financiers including J. P. Morgan, the Du Pont interests, Remington Arms, and others allegedly involved in the plot attempt. As of 1975, a full transcript of the hearings had yet to be traced.[13]

Those accused of the plotting by Butler all denied any involvement. MacGuire was the only figure identified by Butler who testified before the committee. Others involved were actually called to appear to testify, though never were forced to testify.

Partial corroboration of Butler's story

Portions of Butler's story were corroborated by:

- Veterans of Foreign Wars commander James E. Van Zandt. "Less than two months" after General Butler warned him, he said "he had been approached by 'agents of Wall Street' to lead a Fascist dictatorship in the United States under the guise of a 'Veterans Organization.' "[14]

- Captain Samuel Glazier—testifying under oath about plans of a plot to install a dictatorship in the United States.[13] [24]

- Reporter Paul Comly French, reporter for the Philadelphia Record and the New York Evening Post.[25]

Mike Thomson, The Whitehouse Coup, details of a planned coup in the USA in 1933 by right-wing American businessmen

The coup was aimed at toppling President Franklin D Roosevelt with the help of half-a-million war veterans. The plotters, who were alleged to involve some of the most famous families in America, (owners of Heinz, Birds Eye, Goodtea, Maxwell Hse & George Bush’s Grandfather, Prescott) believed that their country should adopt the policies of Hitler and Mussolini to beat the great depression.

Mike Thomson investigates why so little is known about this biggest ever peacetime threat to American democracy.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/history/document/rams/document_20070723.ram

rtsp://rmv8.bbc.net.uk/radio4/history/mon2002_20070723.ra

Earth's magnetic field:

Earth's magnetic field:

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home