Lusitania - Human Shields - Anglo-American Deadly Lies

Secret of the Lusitania: Arms find challenges Allied claims it was solely a passenger ship

By Sam Greenhill

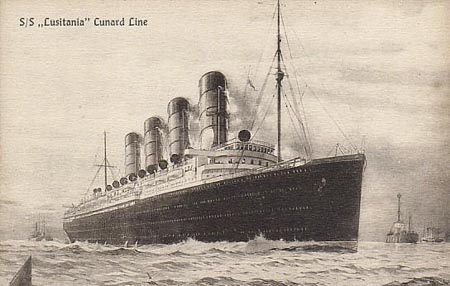

Her sinking with the loss of almost 1,200 lives caused such outrage that it propelled the U.S. into the First World War.

But now divers have revealed a dark secret about the cargo carried by the Lusitania on its final journey in May 1915.

Munitions they found in the hold suggest that the Germans had been right all along in claiming the ship was carrying war materials and was a legitimate military target.

The Cunard vessel, steaming from New York to Liverpool, was sunk eight miles off the Irish coast by a U-boat.

Maintaining that the Lusitania was solely a passenger vessel, the British quickly accused the 'Pirate Hun' of

slaughtering civilians.

The disaster was used to whip up anti-German anger, especially in the U.S., where 128 of the 1,198 victims came from.

A hundred of the dead were children, many of them under two.

Robert Lansing, the U.S. secretary of state, later wrote that the sinking gave him the 'conviction we would ultimately become the ally of Britain'.

Americans were even told, falsely, that German children were given a day off school to celebrate the sinking of the Lusitania.

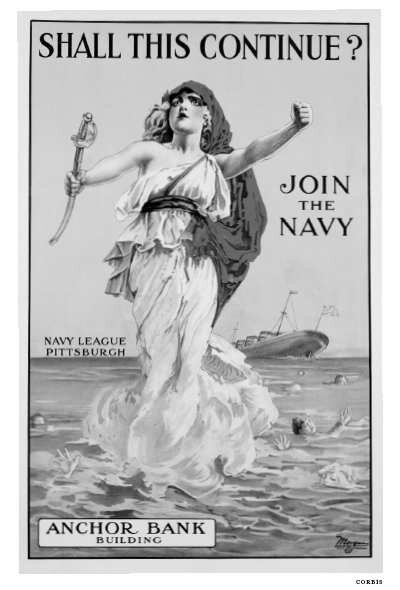

The disaster inspired a multitude of recruitment posters demanding vengeance for the victims.

One, famously showing a young mother slipping below the waves with her baby, carried the simple slogan 'Enlist'.

Two years later, the Americans joined the Allies as an associated power - a decision that turned the war decisively against Germany.

The diving team estimates that around four million rounds of U.S.-manufactured Remington .303 bullets lie in the Lusitania's hold at a depth of 300ft.

The Germans had insisted the Lusitania - the fastest liner in the North Atlantic - was being used as a weapons ship to break the blockade Berlin had been trying to impose around Britain since the outbreak of hostilities in August 1914.

Winston Churchill, who was first Lord of the Admiralty and has long been suspected of knowing more about the circumstances of the attack than he let on in public, wrote in a confidential letter shortly before the sinking that some German submarine attacks were to be welcomed.

He said: 'It is most important to attract neutral shipping to our shores, in the hope especially of embroiling the U.S. with Germany.

'For our part we want the traffic - the more the better and if some of it gets into trouble, better still.'

Hampton Sides, a writer with Men's Vogue in the U.S., witnessed the divers' discovery.

Hampton Sides, a writer with Men's Vogue in the U.S., witnessed the divers' discovery.

He said: 'They are bullets that were expressly manufactured to kill Germans in World War I - bullets that British officials in Whitehall, and American officials in Washington, have long denied were aboard the Lusitania.'

The discovery may help explain why the 787ft Lusitania sank within 18 minutes of a single German torpedo slamming into its hull.

Some of the 764 survivors reported a second explosion which might have been munitions going off.

Gregg Bemis, an American businessman who owns the rights to the wreck and is funding its exploration, said: 'Those four million rounds of .303s were not just some private hunter's stash.

'Now that we've found it, the British can't deny any more that there was ammunition on board. That raises the question of what else was on board.

'There were literally tons and tons of stuff stored in unrefrigerated cargo holds that were dubiously marked cheese, butter and oysters.

'I've always felt there were some significant high explosives in the holds - shells, powder, gun cotton - that were set off by the torpedo and the inflow of water. That's what sank the ship.'

Mr Bemis is planning to commission further dives next year in a full-scale forensic examination of the wreck off County Cork.

RMS Lusitania was a British luxury ocean liner owned by the Cunard Line and built by John Brown and Company of Clydebank, Scotland. Christened and launched on Thursday, 7 June 1906, Lusitania met a disastrous end as a casualty of the First World War when she was torpedoed by the German submarine U-20 on 7 May 1915. The great ship sank in just 18 minutes, eight miles (15 km) off the Old Head of Kinsale, Ireland, killing 1,198 of the people aboard. The sinking turned public opinion in many countries against Germany, and was probably a major factor in the eventual decision of the United States to join the war in 1917. The recent discovery of munitions in the wreck indicates it may have been a blockade runner, and thus a legitimate target. It is often considered by historians to be the second most famous civilian passenger liner disaster after the sinking of Titanic.

Lusitania was approximately 30 miles (48 km) from Cape Clear Island when she encountered fog and reduced speed to 18 knots. She was making for the port of Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland, 70 kilometres (43.5 miles) from the Old Head of Kinsale when the liner crossed in front of U-20 at 14:10.

One story states that when Kapitänleutnant Schwieger of the U-20 gave the order to fire, his quartermaster, Charles Voegele, would not take part in an attack on women and children, and refused to pass on the order to the torpedo room — a decision for which he was court-martialed and served three years in prison at Kiel. However, the story may be apocryphal; Diana Preston writes in Lusitania: An Epic Tragedy that Voegele was an electrician on board U-20 and not a quartermaster.

The torpedo struck Lusitania under the bridge, sending a plume of debris, steel plating and water upward and knocking Lifeboat #5 off its davits, and was followed by a much larger secondary explosion in the starboard bow. Schwieger's log entries attest that he only fired one torpedo, but some doubt the validity of this claim, contending that the German government subsequently doctored Schwieger's log, but accounts from other U-20 crew members corroborate it.

Lusitania's wireless operator sent out an immediate SOS and Captain Turner gave the order to abandon ship. Water had flooded the ship's starboard longitudinal compartments, causing a 15-degree list to starboard. Captain Turner tried turning the ship toward the Irish coast in the hope of beaching her, but the helm would not respond as the torpedo had knocked out the steam lines to the steering motor. Meanwhile, the ship's propellers continued to drive the ship at 18 knots (33 km/h), forcing more water into her hull.

Lusitania's severe starboard list complicated the launch of her lifeboats — those to starboard swung out too far to step aboard safely. While it was still possible to board the lifeboats on the port side, lowering them presented a different problem. As was typical for the period, the hull plates of the Lusitania were riveted, and as the lifeboats were lowered they dragged on the rivets, which threatened to seriously damage the boats before they landed in the water.

Many lifeboats overturned while loading or lowering, spilling passengers into the sea; others were overturned by the ship's motion when they hit the water. It has been claimed that some boats, due to the negligence of some officers, crashed down onto the deck, crushing other passengers, and sliding down towards the bridge. This has been refuted in various articles and by passenger and crew testimony. Lusitania had 48 lifeboats, more than enough for all the crew and passengers, but only six were successfully lowered, all from the starboard side.

Despite Turner's efforts to beach the liner and reduce her speed, Lusitania no longer answered the helm. There was panic and disorder on the decks. Schwieger had been observing this through U-20's periscope, and by 14:25, he dropped the periscope and headed out to sea.

Within six minutes, Lusitania's forecastle began to go under water. Her list continued to worsen and 10 minutes after the torpedoing, she had slowed enough to start putting boats in the water. On the port side, people panicked and got into the boats, even though they were swinging far in from the rails. On the starboard side, the boats were hanging several feet away from the sides. Crewmen would lose their grip on the falls—ropes used to lower the lifeboats—while trying to lower the boats into the ocean, and this caused the passengers from the boat to "spill into the sea like rag dolls." Others would tip on launch as some panicking people jumped into the boat. Of the 48 Lifeboats she carried, only 6 were launched successfully. A few of her collapsible lifeboats washed off her decks as she sank and provided refuge for many of those in the water.

Captain Turner remained on the bridge until the water rushed upward and destroyed the sliding door, washing him overboard into the sea. He took the ship's logbook and charts with him. He managed to escape the rapidly sinking Lusitania and find a chair floating in the water which he clung to. He was pulled unconscious from the water, and survived despite having spent 3 hours in the water. Lusitania's bow slammed into the bottom about 100 m (300 ft) below at a shallow angle due to her forward momentum as she sank. Along the way, some boilers exploded, including one that caused the third funnel to collapse; the remaining funnels snapped off soon after. Turner's last navigational fix had been only two minutes before the torpedoing, and he was able to remember the ship's speed and bearing at the moment of sinking. This was accurate enough to locate the wreck after the war. The ship travelled about two miles (3 km) from the time of the torpedoing to her final resting place, leaving a trail of debris and people behind. After she all the way slipped in the shallow angle, the Lusitania's stern rose out of the water with her propellers could be seen, and went down.

Lusitania sank in 18 minutes, 8 miles (13 km) off the Old Head of Kinsale. 1,198 people died with her, including almost a hundred children. The bodies of many of the victims were buried at either Lusitania's destination, Queenstown, or the Church of St. Multose in Kinsale, but the bodies of the remaining 885 victims were never recovered.

Schwieger was condemned in the Allied press as a war criminal.

Of the 139 US citizens aboard the Lusitania, 128 lost their lives, and there was massive outrage in Britain and America, The Nation calling it "a deed for which a Hun would blush, a Turk be ashamed, and a Barbary pirate apologize" and the British felt that the Americans had to declare war on Germany. However, US President Wilson refused to over-react. He said at Philadelphia on 10 May 1915:

There is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight. There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that it is right

The massive loss of life caused by the sinking of Lusitania required a definitive response from the US. When Germany had began its submarine campaign against Britain, Wilson had warned the US would hold the German government strictly accountable for any violations of American rights.

During the weeks after the sinking, the issue was hotly debated within the administration. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan urged compromise and restraint. The US, he believed, should try to persuade the British to abandon their interdiction of foodstuffs and limit their mine-laying operations at the same time as the Germans were persuaded to curtail their submarine campaign. He also suggested that the US government issue an explicit warning against US citizens travelling on any belligerent ships. Despite being sympathetic to Bryan's antiwar feelings, Wilson insisted that the German government must apologise for the sinking, compensate US victims, and promise to avoid any similar occurrence in the future.

Wilson notes

Backed by State Department second-in-command Robert Lansing, Wilson made his position clear in three notes to the German government issued on 13 May, 9 June, and 21 July.

The first note affirmed the right of Americans to travel as passengers on merchant ships and called for the Germans to abandon submarine warfare against commercial vessels, whatever flag they sailed under.

In the second note Wilson rejected the German arguments that the British blockade was illegal, and was a cruel and deadly attack on innocent civilians, and their charge that the Lusitania had been carrying munitions. William Jennings Bryan considered Wilson's second note too provocative and resigned in protest after failing to moderate it, to be replaced by Robert Lansing who later said in his memoirs that following the tragedy he always had the "conviction that we would ultimately become the ally of Britain".

The third note, of 21 July, issued an ultimatum, to the effect that the US would regard any subsequent sinkings as "deliberately unfriendly".

On 19 August U-24 sank the White Star liner SS Arabic, with the loss of 44 passengers and crew, three of whom were American. The German government, while insisting on the legitimacy of its campaign against Allied shipping, disavowed the sinking of the Arabic; it offered an indemnity and pledged to order submarine commanders to abandon unannounced attacks on merchant and passenger vessels.

German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg persuaded the Kaiser to forbid action against ships flying neutral flags and the U-boat war was postponed once again on 27 August, as it was realised that British ships could easily fly neutral flags.

There was disagreement over this move between the navy's admirals (headed by Alfred von Tirpitz) and Bethman-Hollweg. The Kaiser decided in favour of the Chancellor, backed by Army Chief of Staff Erich von Falkenhayn, and Tirpitz and the head of the admiralty backed down. The German restriction order of 9 September 1915 stated that attacks were only allowed on ships that were definitely British, while neutral ships were to be treated under the Prize Law rules, and no attacks on passenger liners were to be permitted at all. The war situation demanded that there could be no possibility of orders being misinterpreted, and on 18 September Henning von Holtzendorff, the new head of the German Admiralty, issued a secret order: all U-boats operating in the English Channel and off the west coast of the United Kingdom were recalled, and the U-boat war would continue only in the North sea, where it would be conducted under the Prize Law rules.

British propaganda

It was in the interests of the British to keep US passions inflamed, and a fabricated story was circulated that in some regions of Germany, schoolchildren were given a holiday to celebrate the sinking of the Lusitania.

This story was so effective that James W. Gerard, the US ambassador to Germany, recounted it in his memoir of his time in Germany, Face to Face with Kaiserism (1918), though without substantiating its validity.

Goetz medal

In August 1915, Munich medalist and sculptor Karl X. Goetz (1875-1950), who had produced a series of propagandist and satirical medals as a running commentary on the war, privately struck a small run of medals as a limited-circulation satirical attack (fewer than 500 were struck) on the Cunard Line for trying to continue business as usual during wartime. Goetz blamed both the British government and the Cunard Line for allowing the Lusitania to sail despite the German embassy's warnings.

One side of the medal showed the Lusitania sinking laden with guns (incorrectly depicted sinking stern first) with the motto "KEINE BANNWARE!" ("NO CONTRABAND!"), while the reverse showed a skeleton selling Cunard tickets with the motto "Geschäft Über Alles" ("Business Above All".)

Goetz had put an incorrect date for the sinking on the medal, an error he later blamed on a mistake in a newspaper story about the sinking: instead of 7 May, he had put 5 May, two days before the actual sinking. Not realizing his error, Goetz made copies of the medal and sold them in Munich and also to some numismatic dealers with whom he conducted business.

The British Foreign Office obtained a copy of the medal, photographed it, and sent copies to the United states where it was published in the New York Times on 5 May 1916, the anniversary of the sinking. Many popular magazines ran photographs of the medal, and it was falsely claimed that it had been awarded to the crew of the U-boat.

British replica

The Goetz medal attracted so much attention that Lord Newton, who was in charge of Propaganda at the Foreign Office in 1916, decided to exploit the anti-German feelings aroused by it for propaganda purposes and asked department store entrepreneur Harry Gordon Selfridge to reproduce the medal. The replica medals were produced in an attractive case claiming to be an exact copy of the German medal, and were sold for a shilling apiece. On the cases it was stated that the medals had been distributed in Germany "to commemorate the sinking of the Lusitania" and they came with a propaganda leaflet which strongly denounced the Germans and used the medal's incorrect date to claim that the sinking of the Lusitania was premeditated. The head of the Lusitania Souvenir Medal Committee later estimated that 250,000 were sold, proceeds being given to the Red Cross and St. Dunstan's Blinded Soldiers and Sailors Hostel. Unlike the original Goetz medals which were stamped from bronze, the British copies were of diecast iron and were of poorer quality.

Belatedly realizing his mistake, Goetz issued a corrected medal with the date of 7 May. The Bavarian government suppressed the medal and ordered their confiscation in April 1917. The original German medals can easily be distinguished from the English copies because the date is in German; the English version was altered to read 'May' rather than 'Mai'. After the war Goetz expressed his regret his work had been the cause of increasing anti-German feelings, but it remains one of the most celebrated propaganda acts of all time.

While the American public and leadership were not ready for war, the path to an eventual declaration of war had been set as a result of the sinking of the Lusitania.

Last living survivor

Audrey Lawson-Johnston (née Pearl) (born 1915) is the last living survivor of the RMS Lusitania sinking. She is widowed and resides in Bedfordshire, England. Audrey became the last living survivor following the death of Barbara McDermott (nee Anderson) on 12 April 2008 and Ida Cantley on 31 December 2006.

Controversies

Contraband and second explosion

| | This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2008) |

Under the "cruiser rules", the Germans could sink a civilian vessel only after guaranteeing the safety of all the passengers. Since Lusitania (like all British merchantmen) was under instructions from the British Admiralty to report the sighting of a German submarine, and indeed to attempt to ram the ship if it surfaced to board and inspect her, she was acting as a naval auxiliary, and was thus exempt from this requirement and a legitimate military target. By international law, the presence (or absence) of military cargo was irrelevant.

Lusitania was in fact carrying small arms ammunition, which would not have been explosive. Included in this cargo were 4,200,000 rounds of Remington 0.303 rifle cartridges, 1250 cases of 3 inch (76 mm) fragmentation shells, and eighteen cases of fuses. (All were listed on the ship's two-page manifest, filed with U.S. Customs after she departed New York on 1 May.) However, the materials listed on the cargo manifest were small arms and the physical size of this cargo would have been quite small. These munitions were also proven to be non-explosive in bulk, and were clearly marked as such. It was perfectly legal under American shipping regulations for her to carry these; experts agreed they were not to blame for the second explosion. Allegations the ship was carrying more controversial cargo, such as fine aluminium powder, concealed as cheese on her cargo manifests, have never been proven. Recent expeditions to the wreck have shown her holds are intact and show no evidence of internal explosion.

In 1993, Dr Robert Ballard, the famous explorer who discovered Titanic, conducted an in-depth exploration of the wreck of Lusitania. Ballard found Light had been mistaken in his identification of a gaping hole in the ship's side. To explain the second explosion, Ballard advanced the theory of a coal-dust explosion. He believed dust in the bunkers would have been thrown into the air by the vibration from the explosion; the resulting cloud would have been ignited by a spark, causing the second explosion. In the years since he first advanced this theory, it has been argued that this is nearly impossible. Critics of the theory say coal dust would have been too damp to have been stirred into the air by the torpedo impact in explosive concentrations; additionally, the coal bunker where the torpedo struck would have been flooded almost immediately by seawater flowing through the damaged hull plates.

More recently, marine forensic investigators have become convinced an explosion in the ship's steam-generating plant is a far more plausible explanation for the second explosion. There were very few survivors from the forward two boiler rooms, but they did report the ship's boilers did not explode; they were also under extreme duress in those moments after the torpedo's impact, however. Leading Fireman Albert Martin later testified he thought the torpedo actually entered the boiler room and exploded between a group of boilers, which was a physical impossibility. It is also known the forward boiler room filled with steam, and steam pressure feeding the turbines dropped dramatically following the second explosion. These point toward a failure, of one sort or another, in the ship's steam-generating plant. It is possible the failure came, not directly from one of the boilers in boiler room no. 1, but rather in the high-pressure steam lines to the turbines. Most researchers and historians agree that a steam explosion is a far more likely cause than clandestine high explosives for the second explosion.

The original torpedo damage alone, striking the ship on the starboard coal bunker of boiler room no. 1, would probably have sunk the ship without a second explosion. This first blast was enough to cause, on its own, serious off-center flooding. The deficiencies of the ship's original watertight bulkhead design exacerbated the situation, as did the many portholes which had been left open for ventilation.

Recent developments

The wreck of Lusitania is currently owned by New Mexico diver and businessman F. Gregg Bemis Jr.

In 1967 the wreck was sold by the Liverpool & London War Risks Insurance Association to former US Navy diver John Light, for £1,000. Bemis became a co-owner of the wreck in 1968, and by 1982 Bemis had bought out his partners to become sole owner. He subsequently went to court in England in 1986, the US in 1995, and Ireland in 1996 to ensure his ownership was legally watertight.

None of the jurisdictions objected to his ownership of the vessel but in 1995 the Irish Government declared it a heritage site under the National Monuments Act, which prohibited him from in any way interfering with it or its contents. After a protracted legal wrangle, the Supreme Court in Dublin overturned the Arts and Heritage Ministry's previous refusal to issue Bemis with a five year exploration licence in 2007, ruling that the then minister for Arts and Heritage had misconstrued the law when he refused Bemis's 2001 application. Bemis planned to dive and recover and analyse whatever artifacts and evidence can help piece together the story of what happened to the ship. He says that any items found will be given to museums following analysis. Any fine art recovered, such as the Rubens rumoured to be on board, will remain in the ownership of the Irish Government.

In late July 2008 Gregg Bemis was granted an "imaging" license by the Department of the Environment, which allows him to photograph and film the entire wreck, and should allow him to produce the first high-resolution pictures of it. Bemis plans to use the data gathered to assess the wreck's deterioration and to plan a strategy for a forensic examination of the ship, which he estimated would cost $5m. Florida-based Odyssey Marine Exploration (OME) have been contracted by Bemis to conduct the survey. The Department of the Environment's Underwater Archaeology Unit will join the survey team to ensure that research is carried out in a non-invasive manner. A film crew from the Discovery Channel will also be on hand. A documentary will be shown on the network in the next year.

A dive team from Cork Sub Aqua Club, under license, made the first known discovery of munitions aboard in 2006. These include 15,000 rounds of .303 (7.7×56mmR) caliber rifle ammunition in boxes in the bow section of the ship. The .303 round was used by the British army in all of their battlefield rifles and machine guns. The find was photographed but left in situ under the terms of the license. In December 2008, Gregg Bemis discovered a further four million rounds of .303 ammunition and announced plans to commission further dives next year for a full-scale forensic examination of the wreck. The new discovery bolsters the Germans' case that the Lusitania was a military ship.

In 2007, an English - German coproduction, the ninety-minute docu-drama "Lusitania: Murder on the Atlantic", was made.

The sinking of Lusitania to ravage British and American treasuries 15.12.2008

Source: Pravda.Ru

Divers made a sensational discovery during the examination of the Lusitania ocean liner which sank in 1915. They confirmed the version, according to which Britain and the USA used civil passenger vessels to smuggle arms, jeopardizing the lives of thousands of civilians. The passengers of the liner were virtually used as the human shield in the event the liner was going to be attacked by the German navy.

The divers found war supplies on board the Lusitania liner, which sank on May 7, 1915 off the coast of Ireland. Most of the passengers – 1,198 people, including 139 American citizens – were killed in the tragedy. The event, which the media described as the largest military crime in history, sparked numerous protests in the world and had the USA involved in WWI.

Europe found itself in the middle of an arms race on the threshold of WWI. Great Britain tried to mislead the enemy regarding its military power. The country was building both conventional and reserve battleships that were guised under civil vessels. The latter included large ocean liners, which Britain planned to use within the structure of its navy in case of necessity. The 31,000-tonnage Lusitania was one of the largest ships of that time.

Indeed, cannon platforms and ammunition hoists were mounted on the Lusitania and other vessels of the type as soon as the war broke out. However, Britain was forced to give up the original idea of their usage because of the fear of the ‘newest German weapon’ – submarines, for which a large ocean liner was a very good target. Once mobilized for military purposes, the Lusitania became a plain, albeit a huge, passenger ocean liner again.

The British industry found itself not ready for the world war and was unable to meet the demands of the nation’s defense industry. The ocean liners were eventually used as contraband ships. The Lusitania sailed on her deadly voyage from New York to Liverpool on May 1, 1915. A German U-20 submarine torpedoed the liner a week later.

The German media immediately wrote that there were explosive substances and military hardware on board the liner. Britain and the United States rejected the affirmation.

Needless to say that the truth about the ocean liner would have remained a mystery for it was extremely difficult to submerge at the depth of over 100 meters, where the Lusitania was resting. Things have changed nowadays. It turned out that the ship was carrying many cases of Remington bullets.

Earth's magnetic field:

Earth's magnetic field:

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home