part 3 - Bill Arkin "Top Secret America"

"Top Secret America"

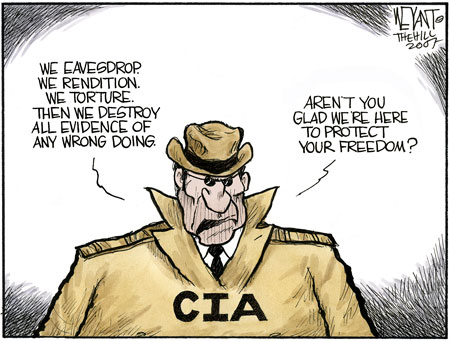

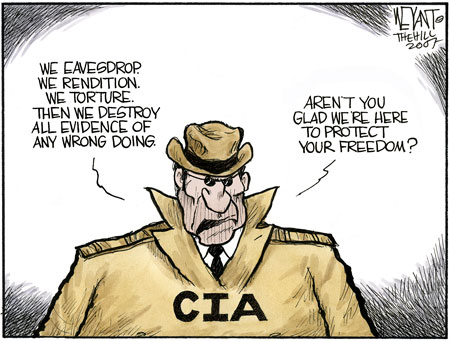

STASI GESTAPO Version 2.0

Washington Post Investigation Reveals Massive, Unmanageable, Outsourced US Intelligence System

An explosive investigative series published in the Washington Post today begins, "The top-secret world the government created in response to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, has become so large, so unwieldy and so secretive that no one knows how much money it costs, how many people it employs, how many programs exist within it or exactly how many agencies do the same work." Among the findings: An estimated 854,000 people hold top-secret security clearances. More than 1,200 government organizations and nearly 2,000 private companies work on programs related to counterterrorism, homeland security and intelligence in 10,000 locations. We speak with one of the co-authors of the series, Bill Arkin.

LISTEN to this (easier than reading!)

http://traffic.libsyn.com/democracynow/dn2010-0719-1.mp3

AMY GOODMAN: "Top Secret America." That's the title of an explosive investigative series published in the Washington Post this morning that's already creating a firestorm on Capitol Hill. It starts, quote, "The top-secret world the government created in response to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, has become so large, so unwieldy and so secretive that no one knows how much money it costs, how many people it employs, how many programs exist within it or exactly how many agencies do the same work."

Some of the findings of the two-year investigation include more than 1,200 government organizations and nearly 2,000 private companies work on programs related to counterterrorism, homeland security and intelligence in about 10,000 locations across the United States. An estimated 854,000 people—nearly one-and-a-half times as many as live in Washington, DC—hold top-secret security clearances. Many security and intelligence agencies do the same work, creating redundancy and waste.

The series by Washington Post reporters Dana Priest and Bill Arkin includes an online searchable database and locator map. PBS Frontline is producing an hour-long documentary on the investigation that will run in October. This is its trailer.

NARRATOR: You think you know America. But you don't know Top Secret America. We're all aware that there are three branches of government in the United States. But in response to 9/11, a fourth branch has emerged. It is protected from public scrutiny by extraordinary secrecy. Top Secret America.

WILLIAM ARKIN: This is a closed community. And since 9/11, it's become even more so.

DANA PRIEST: The money spigot was just opened after 9/11, and nobody dared say, "I don't think we should be spending that much."

NARRATOR: It has become so big, and the lines of responsibility are so blurred, that even our nation's leaders don't have a handle on it. Where is it? It's being built from coast to coast, hidden within some of America's most familiar cities and neighborhoods—in Colorado, in Nebraska, in Texas, in Florida, in the suburbs of Washington, DC. Top Secret America includes hundreds of federal departments and agencies operating out of 1,300 facilities around this country. They contract the services of nearly 2,000 companies. In all, more people than live in our nation's capital have top-secret security clearance.

DANA PRIEST: It's, again, the size, the lack of transparency and the cost. And if we don't get it right, the consequences are gigantic.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Washington Post writer Dana Priest, the trailer from the upcoming PBS Frontline documentary on "Top Secret America" that features Priest and Bill Arkin.

The investigative series is already creating waves in the intelligence community. More than two weeks ago, the director of communications for the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, Art House, sent a memo to public affairs officers in the intelligence community warning about the series. He wrote, quote, "This series has been a long time in preparation and looks designed to cast the [intelligence community] and the [Department of Defense] in an unfavorable light. We need to anticipate and prepare so that the good work of our respective organizations is effectively reflected in communications with employees, secondary coverage in the media and in response to questions," he wrote.

Well, Bill Arkin is the co-author of the piece. He's joining us now from the offices of the Washington Post in Washington, DC.

Welcome to Democracy Now!, Bill. Why don't you first lay out the scope of this series and why you started this two years ago?

WILLIAM ARKIN: Well, two years ago, Dana and I got together, and we were actually just talking to each other about various things that we were working on, and we realized very quickly that we were looking at something that was very similar and that we had both detected in our long years of work in the national security world that something had been created since 9/11 that wasn't normal, that wasn't on the books, that looked like it was a gigantic superstructure on top of regular government. And we started our investigation to try to figure out what it is that we were looking at, and here we are two years later revealing our conclusions.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about what those conclusions are. What did you find, Bill?

WILLIAM ARKIN: Well, really, the most significant thing that we found, Amy, is not that the intelligence agency or the vast homeland security apparatus does work in this field and that is—and that they are engaged in counterterrorism. Really the most significant finding, to me, is the number of private companies in America who have been enlisted in the war on terrorism and who have now become an intrinsic part of government, really where the line is blurred between government and private sector. And the fact that there are almost 2,000 companies that do top-secret work in—for the intelligence community and the military is not only surprising to me as someone who actually put together the data, but it really asks some fundamental questions about the nature of government and the nature of accountability.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about these 2,000 companies.

WILLIAM ARKIN: Well, you know, it's funny. We think of the military-industrial complex in a sort of old-fashioned way still. In fact, we don't even have an appropriate word to describe what this enterprise is today, and we've struggled ourselves to try to figure that out. You know, the military-industrial complex of the Eisenhower era was one that produced massive amounts of capital goods for the military—bombers, missiles, nuclear weapons, etc. But today's national security establishment really values information technology more than it values weapons. And really, one of the things that was most surprising to us, but maybe not so surprising given the nature of society, is that a half of the companies in this particular area are really IT companies, information technology companies, and support companies.

The domination of this world of top-secret contractors over the traditional world of the military-industrial complex is huge. And we see very clearly that the megacorporations which have always been the powerhouses in the defense industry—Northrop Grumman, General Dynamics—they are moving more and more of their business from production to the provision of services—that is, providing staffing for the government. And so, what you see is that we are increasingly a national security establishment that's producing paper rather than producing weapons. And the question is, with the production of all that paper, whether or not we have either an effective counterterrorism operation or whether or not we're even safer.

AMY GOODMAN: So, what about the privatization of top-secret information or the people around the country who have access to top-secret information, especially when they're working in a private corporation?

WILLIAM ARKIN: You know, one thing that we found in the evidence, Amy, is that people who are in business are in business. I'm not going to say that they're not good Americans, any less than we are, but it seems to me that their fundamental mission is to make money for their businesses. And that is not the same as being a public servant. And as you can see from our articles, we have quotes from all of the principals involved, on the record—Secretary Gates; Leon Panetta, the CIA director; the Director of Defense Intelligence and the former Director of National Intelligence, Admiral Blair—essentially agreeing with us that this crazy, out-of-control system accreted after 9/11, and here, two years into the Obama administration, it is essentially in the same form that it was when the Bush administration left office. But there is something fundamentally wrong in America if you have people who are working in a for-profit environment caring for our national security and engaged in what we consider to be the inherent functions of government.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, it is amazing that there are more people who have top-security clearance in this country than live in Washington, DC—more than 850,000 people.

WILLIAM ARKIN: Well, it is. It's a good comparison. But I also think that what we find is that, more and more, Washington is not just the hub of government, but it is also the hub of this sort of intelligence information enterprise. You see gigantic companies like SAIC and Northrop Grumman moving their headquarters from California to the Washington, DC metropolitan area, and you know that with that comes not only thousands of workers and thousands of people whose job it is to secure contracts to do government work, but also the vast infrastructure that is required in order to secure the secrets and to do all of those things that are necessary in order to be in this hidden world. And so, more and more is being concentrated in Washington. And that's undeniable. We show it very clearly in our series, and the data really backs it up. And I think it's probably part of why there's such an enormous groundswell throughout the United States that is so anti-Washington these days.

AMY GOODMAN: Bill Arkin, what's a Super User?

WILLIAM ARKIN: Well, what we discovered in the course of our investigation is that not only are there top secrets, but there are various compartments above the level of top secret which are utilized by each of the intelligence agencies and the military commands to compartment what they do. And intrinsically, that's supposed to be to protect information, but in reality, what it does is it keeps programs from being revealed to other agencies. And in theory, above it all is supposed to be the Director of National Intelligence, an office created in 2004 to finally solve the problems of 9/11. But what we found was that even the Director of National Intelligence and even the Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence, the top intelligence official in the government, that they don't have full visibility on each other's programs, and they don't have full visibility on everything even within their own agency.

And there's this thing called Super Users, people who are designated specially who have the ability to reach into all of the programs of all of the government. They actually have special logins. They actually have special computers. And there's only a few dozen of them, as far as we can determine, throughout the entire government, only a half-dozen or so in the Defense Department and only a half-dozen in the Director of National Intelligence. And we've spoken to some of those Super Users who themselves say, "I don't have enough hours in the day to look at all the programs of the US government. I don't have enough—I don't have enough time to read all of the material that I am authorized to read." And so, you can really see in a very vivid way the dysfunction of government through this little anecdote.

AMY GOODMAN: Bill Arkin, talk about the warning, the letter that was sent around to the intelligence community from Art House—and explain who he is—warning them of this series of pieces that you and Dana Priest are doing.

WILLIAM ARKIN: Well, let me just make it clear, Amy, we've been working on this for two years. We've been engaged in interviewing people from the government and inside this world for two years. We've conducted over a thousand interviews, talked to hundreds of people, many multiple times. They were well aware of what we were doing, and we formally briefed them about this earlier this year. So for them to come out at the eleventh hour and somehow say that they are alarmed by what we're going to put out, to me, seems to be classic cover-your-ass. I can't take it in any other way, because we ourselves have gone through a massive internal review process, both fact checking and also looking at anything that could be detrimental to the national security interest and to the national interest, and I'm completely confident that we've done a rigorous job. I'm completely confident, through the use of numerous outside counsels at the Washington Post, people who are insiders to the system, helping us to make sure that we were able to produce the most granular picture we possibly could of this gigantic organization, but yet at the same time not put anybody's life at risk. And I have to say at this point, I feel like the Washington Post has a better understanding of this overall problem than the government does.

AMY GOODMAN: What is it they did not want you to print, Bill?

WILLIAM ARKIN: Well, they always don't want you to do whatever it is that's going to bring them—you know, that's going to disrupt their day. You know, the government, we asked them repeatedly to give us specifics, to tell us what it is that they didn't want us to show. And only one government agency was actually able to come back to us and specifically explain to us why they didn't want us to reveal something, and they made a reasonable argument to the editors, and the editors decided that we wouldn't.

This is such a rich area that we felt that really to diminish it by somehow not looking at these requests from the government seriously was a mistake. We're giving you information on 1,931 corporations, on 1,271 government entities across forty-five different departments and agencies. I mean, this is an enormous amount of information. And Secretary Gates himself said to us in an interview that he can't even get this type of information about his own office and who contracts all of the contractors within his own office. People recognize that this is a problem, and I think that the Washington Post should really be given an enormous amount of credit for putting the resources into this over a two-year period in order to present something that I hope will be the foundation of a new national debate about this whole question.

AMY GOODMAN: Bill Arkin, what's Liberty Crossing?

WILLIAM ARKIN: Liberty Crossing is the name, the nickname, for the new complex of buildings that has gone up in McLean, Virginia, that is home to the Director of National Intelligence, the CIA's National Counterterrorism Center, other counterterrorism task forces, and the National Counterproliferation Center. We highlight the buildings around Washington that have been created since 9/11, because we thought that it was a very tangible representation of government. It's often hard to really talk about government in terms of money, because the billions, after a while, begin to just glaze over. But we thought—you know, our approach was going to be, we know that everything that happens happens somewhere, and we're going to find out where it happens. And lo and behold, as we began to map this alternative geography of America, one of the things we discovered was that these guys have been on a fabulous building spree since 9/11. There have been over thirty-three buildings in the Washington, DC area alone, encompassing 17 million square feet, which is four times the size of the Pentagon, and there are more underway. The NSA and others are building and planning to build even more office space. So the reality is that—I think in my research I found that there was only one civilian agency that's had the privilege of building a new headquarters since 9/11 in Washington, and that's the Department of Transportation. But this is a very tangible way of seeing this in your backyard, in reality, in a real physical location.

And one of the phenomena that is also associated with 9/11 is that these locations, like Liberty Crossing, are undisclosed locations, meaning you can't look them up in a phone book. It has a cover address. It's not publicly bragged about, in terms of where it is, although it's obvious where it is to anyone who goes by. And that in itself is sort of an odd manufacture from 9/11, which is that these government agencies, on their own, with really no consideration of national security, can just decide what's going to be disclosed, what's going to be undisclosed. And as far as I can see, it's random to the agency and its power, and it has nothing to actually do with the security of the buildings or the people who work inside them.

AMY GOODMAN: The National Geospatial Intelligence Agency, the new $1.8 billion headquarters, the fourth-largest federal building in the area, in Springfield, right near Dulles Airport?

WILLIAM ARKIN: No, in Springfield, Virginia, it's down south near Fort Belvoir. This is a gigantic facility that's going to—that's going up right now. It's going to house 8,500 workers of the

National Geospatial Intelligence Agency. I mean, they are going to leave their older buildings that are scattered throughout Washington. But you know what? They're going to be in well-appointed offices, and they'll be in one facility in Washington, and they will obviously, I assume, be able to do their work better. But it's just one of many. It's just one of many agencies that probably most Americans have never heard of within the national security and intelligence establishment. And as we found, you know, there are thirty-nine new construction starts this year alone nationwide of buildings going up for various pieces of the intelligence, homeland security and military communities.

AMY GOODMAN: The growth of the military budget, Bill Arkin, since 9/11?

WILLIAM ARKIN: Well, you know, it's hard to say even what we spend on national security anymore, Amy. I guess we say we spend a half-a-trillion dollars now on national security. But with supplemental budgets and secret budgets and all that, I mean, it's really impossible to be able to put a true figure on it. And more importantly, it's really impossible to gauge where this money is actually going and how effective it is. We've talked to people on the Hill who have said to us that the budget documents get thinner and thinner as the budget gets bigger and bigger. There's no way that Capitol Hill has the resources or the ability to oversee all of this activity. And all sorts of workarounds and devices have been created since 9/11 to essentially put as much as possible into secret programs or off-the-books programs so that they're beyond scrutiny. Maybe there'll be eight people in the Congress who have the authority to see the information, but, you know, that's not oversight as it's written in the Constitution. Those are people who are co-opted into the system. And I think that really this is an issue that we, as Americans, need to ponder, that we have created a government apparatus that really does not comply with our very precept of the balance of powers. And that's something that I hope that our series will provoke Congress to take a hard look at, in terms of thinking about better ways in which it can exercise its oversight responsibilities over the executive branch.

AMY GOODMAN: Bill, you've been doing this kind of work for years. What were you most shocked by in this latest investigation?

WILLIAM ARKIN: I remember having a conversation with Dana, my writing partner, in the summer of 2009. We had sort of started by looking at the government and then shifted our attention to looking at the contracting base. And I said, "Wow! There's 200 companies that do top-secret work for the government." And now we're at 2,000. I mean, it is the sheer magnitude of it, Amy, that is stunning. And to me, you know, it's not that there might not be redundancies that are necessary or that there might not be overlap which is necessary and disparate departments doing disparate things.

And many of the conclusions that we draw, I think, are ones that your viewers and listeners would accept readily and are part of their normal discussions of government. But the truth is that no one really has a handle on it all. No one really does. We've talked to the people at the highest level. We've talked to the principals involved, and they have all readily admitted that, yes, this ad hoc crazy system was created after 9/11. We threw money at the problem. We did it the American way, Admiral Blair said to us. You know, if it's worth doing, it's worth overdoing. I mean, ha ha, but the truth of the matter is that now we're two years into the Obama administration, and the basic system really has not been reformed at all.

AMY GOODMAN: Lay out for us what we will see over the next two days—this is a three-part series—and also the database that you have collated. What is online at washingtonpost.com?

WILLIAM ARKIN: Well, this is a very rich digital journalism project. I would almost go as far to say that this is a digital product with a small print component to it. As much as the Washington Post has allocated five pages to the newspaper today to our first in this series, the online presentation includes a link analysis application, which will allow you to look at government agencies and look at functions and see how many contractors work for them at the top-secret level and at how many locations and to look at some of the featured companies that we discuss in the article series and look at who they work for and some of their locations. There's also a mapping application that allows you to delve into the presence of Top Secret America in your own community. And then there is a profile of each of those 3,000-plus entities, where you can look in more detail at their revenue, the size of the companies, and what it is that they do in this field.

So we've provided, as is the nature of the internet, the actual backup material to do it. But it wasn't a second thought to the stories. It wasn't like we wrote stories and then said, "Let's put a web presentation together." From the very inception of this project, we have worked in unison with the website, and we've had a team of over thirty people working with us, and that's an enormous amount of resources these days in the mainstream media, to be able to have really what we consider to be the future of investigative journalism displayed in these various multimedia ways with documentary footage, with photo galleries, with a database that's searchable. We have a Facebook page. And there is a URL, topsecretamerica.com, where you can see our blog that'll launch today and that we'll be starting to write on on Thursday, as well as online discussions and other comments and commentary from our readers.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Bill, I want to thank you very much for being with us. Bill Arkin, a reporter for the Washington Post, co-authored this investigative series that has just been released today in the Washington Post called "Top Secret America." We'll link to it at democracynow.org

LISTEN to this (easier than reading!)

This is an authentic poster from the 1930s!

Top Secret America | Cash cow for contractors

topsecretamerica.com

By Dana Priest and William M. Arkin

The Washington Post

The top-secret world the government created in response to the Sept. 11 attacks is so large, so unwieldy and so secretive that no one knows how much money it costs, how many people it employs, how many programs exist or how many agencies do the same work.

These are some of the findings of a two-year investigation that discovered what amounts to an alternative geography of the United States, a Top Secret America hidden from public view and lacking in thorough oversight. After nine years of unprecedented spending and growth, the result is that the system put in place to keep the United States safe is so massive that its effectiveness is impossible to determine.

The investigation's other findings:

• Some 1,271 government organizations and 1,931 private companies work on programs related to counterterrorism, homeland security and intelligence in some 10,000 U.S. locations.

• An estimated 854,000 people hold top-secret security clearances.

• In the Washington, D.C., area, 33 building complexes for top-secret intelligence work are under construction or have been built since September 2001.

• Many agencies do the same work, creating redundancy and waste. For example, 51 federal organizations and military commands, operating in 15 U.S. cities, track the flow of money to and from terrorist networks.

• Analysts who make sense of documents and conversations obtained by foreign and domestic spying share their judgment by publishing 50,000 reports each year; many are routinely ignored.

These issues greatly concern people in charge of the nation's security.

"There has been so much growth since 9/11 that getting your arms around that — not just for the DNI (Director of National Intelligence), but for any individual, for the director of the CIA, for the secretary of defense — is a challenge," Defense Secretary Robert Gates said.

In the Defense Department, where more than two-thirds of intelligence programs reside, a handful of senior officials — called Super Users — even know about all the department's activities. But as two of the Super Users indicated, there is simply no way they can keep up with the nation's most sensitive work.

"I'm not going to live long enough to be briefed on everything" was how one Super User put it. The other recounted his initial briefing: Program after program began flashing on a screen, he said, until he yelled "Stop!"

Asked last year to review the method for tracking the Defense Department's most sensitive programs, retired Army Lt. Gen. John Vines said, "I'm not aware of any agency with the authority, responsibility or a process in place to coordinate all these interagency and commercial activities."

The result, he added, is that it's impossible to tell whether the country is safer.

Gates said he does not believe the system has become too big to manage but that getting precise data is sometimes difficult. He said he intends to review intelligence units in the Defense Department for waste.

CIA Director Leon Panetta said he's begun mapping a five-year plan for his agency because the spending since 9/11 is not sustainable. "Particularly with these deficits, we're going to hit the wall. I want to be prepared for that," he said.

Before resigning as director of national intelligence in May, retired Adm. Dennis Blair said he did not believe there was overlap and redundancy in the intelligence world. "Much of what appears to be redundancy is, in fact, providing tailored intelligence for many different customers," said Blair, who expressed confidence that subordinates told him what he needed to know.

854,000 on a mission

Every day, 854,000 civil servants, military personnel and private contractors with top-secret security clearances are scanned into offices protected by electromagnetic locks, retinal cameras and fortified walls.

Much information about this mission is classified. That is one reason it is so difficult to gauge the success and identify the problems of Top Secret America, including whether money is spent wisely. The U.S. intelligence budget is vast, publicly announced last year as $75 billion — 2 ½ times the size it was on Sept. 10, 2001. That doesn't include many military activities or domestic counterterrorism programs.

At least 20 percent of the government organizations that exist to fend off terrorist threats were established or refashioned after 9/11. Many that existed before grew to historic proportions as the Bush administration and Congress gave agencies more money than they could spend responsibly.

Nine days after the attacks, Congress committed $40 billion beyond what was in the federal budget. It followed that up with an additional $36.5 billion in 2002 and $44 billion in 2003. That was only a beginning.

Twenty-four organizations were created by the end of 2001, including the Office of Homeland Security and the Foreign Terrorist Asset Tracking Task Force. In 2002, 37 more were created to track weapons of mass destruction, collect threat tips and coordinate the new focus on counterterrorism. That was followed the next year by 36 new organizations; and 26 after that; and 31 more; and 32 more; and 20 or more each in 2007, 2008 and 2009.

In all, at least 263 organizations have been created or reorganized.

With so many more employees, units and organizations, lines of responsibility began to blur. To remedy this, at the recommendation of the bipartisan 9/11 Commission, the Bush administration and Congress in 2004 created the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) to bring the colossal effort under control.

A couple of problems

The first problem: The law passed did not give the director clear legal or budgetary authority over intelligence matters, which meant he wouldn't have power over the individual agencies he was supposed to control.

The second problem: Even before the first director, Ambassador John Negroponte, was on the job, turf battles began. The Defense Department shifted billions of dollars out of one budget and into another so the ODNI could not touch it, according to two senior officials. The CIA reclassified some of its most sensitive information so the National Counterterrorism Center staff, part of the ODNI, would not be allowed to see it, former intelligence officers said.

Many intelligence officials say they remain unclear about what the ODNI is in charge of.

The increased flow of intelligence data overwhelms the system's ability to analyze and use it. Every day, collection systems at the National Security Agency intercept and store 1.7 billion e-mails, phone calls and other types of communications. The NSA sorts a fraction of those into 70 databases. The same problem bedevils every other intelligence agency.

The explanation for why these databases aren't connected: It's too hard, and some agency heads don't want to give up their systems.

Clusters of top-secret work exist across the country, but about half of the post-9/11 enterprise is anchored in the Washington region. Many buildings sit within off-limits compounds or military bases. Others occupy business parks or are intermingled with neighborhoods, schools and shopping centers and go unnoticed by most people.

It's not only the number of buildings that suggests the size and cost, it's also what is inside: banks of television monitors. "Escort-required" badges. X-ray machines and lockers to store cellphones and pagers. Keypad door locks that open special rooms encased in metal or permanent dry wall, impenetrable to eavesdropping tools and protected by alarms and a security force. All these buildings have at least one of these rooms, known as a SCIF, for sensitive compartmented information facility.

SCIFs are not the only must-have items people pay attention to. Command centers, internal television networks, video walls, armored SUVs and personal security guards have also become the bling of national security.

Among the most important people inside the SCIFs are the low-paid employees. They are the analysts, the 20- and 30-year-olds making $41,000 to $65,000 a year.

The work is enhanced by computers. But analysis requires human judgment, and half the analysts are relatively inexperienced, a senior ODNI official said.

When hired, a typical analyst knows little about the priority countries — Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan — and is not fluent in their languages. Still, the number of intelligence reports they produce on these key countries is overwhelming, say current and former intelligence officials.

The problem, say officers who read these reports, is they simply re-slice the facts already in circulation.

The ODNI's analysis office knows this is a problem. Yet its solution was another publication, a daily online newspaper, Intelligence Today.

Analysis is not the only area where serious overlap appears to be gumming up the national-security machinery.

Within the Defense Department alone, 18 commands and agencies conduct the most sensitive information operations, which aspire to manage foreign audiences' perceptions of U.S. policy and military activities.

And all the major intelligence agencies and at least two major military commands claim a major role in cyber-warfare, the newest and least-defined frontier.

"Frankly, it hasn't been brought together in a unified approach," CIA Director Panetta said.

Beyond redundancy, secrecy within the intelligence world hampers effectiveness in other ways, say defense and intelligence officers. For the Defense Department, the root of this problem goes back to an ultra-secret group of programs for which access is extremely limited and monitored by specially trained security officers.

These are called Special Access Programs — or SAPs — and the Pentagon's list of code names for them runs 300 pages. The intelligence community has hundreds more, and those have thousands of sub-programs with limits on the people authorized to know about them.

"There's only one entity in the entire universe that has visibility on all SAPs — that's God," said James Clapper, undersecretary of defense for intelligence and the Obama administration's nominee to be the next director of national intelligence.

Near disaster in Detroit

A recent example shows the post-9/11 system at its best and its worst.

Last fall, word emerged that something was seriously amiss inside Yemen. President Obama signed an order sending dozens of commandos to target and kill leaders of an al-Qaida affiliate.

In Yemen, the commandos exchanged thousands of intercepts, agent reports, photographic evidence and real-time video surveillance with dozens of top-secret organizations in the U.S.

But when the information reached the National Counterterrorism Center for analysis, it was buried within the 5,000 pieces of general terrorist-related data that are reviewed each day. Analysts had to switch from database to database, from hard drive to hard drive, from screen to screen, just to locate it.

As chatter about a possible terrorist strike increased, the flood of information into the NCTC became a torrent.

Somewhere in that deluge was even more vital data. Partial names of someone in Yemen. A reference to a Nigerian radical who had gone to Yemen. A report of a father in Nigeria worried about a son who had become interested in radical teachings.

But nobody put the clues together because, as officials would testify, the lines of responsibility had become hopelessly blurred.

And so a Nigerian named Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab was able to step aboard Northwest Airlines Flight 253 in Amsterdam. As it neared Detroit, he allegedly tried to ignite explosives hidden in his underwear. The very expensive, very large 9/11 enterprise didn't prevent disaster. It was a passenger who tackled him.

Blair's solution: Create another team, more money and more analysts.

In June, a stone carver chiseled another star into a marble wall at CIA headquarters, one of 22 for agency workers killed in the global war initiated by the Sept. 11 attacks.

The intent of the memorial is to publicly honor the courage of those who died in the line of duty, but it also conceals a deeper story about government in the post-9/11 era: Eight of the 22 were not CIA officers. They were private contractors.

To ensure that the country's most sensitive duties are carried out only by people loyal above all to the nation's interest, federal rules say contractors may not perform what are called "inherently government functions." But they do all the time, in every intelligence and counterterrorism agency, according to a two-year investigation.

What started as a temporary fix in response to the terrorist attacks has turned into a dependency that calls into question whether the federal work force includes too many people obligated to shareholders rather than the public interest and whether the government is still in control of its most sensitive activities. Defense Secretary Robert Gates and CIA Director Leon Panetta last week said they agreed with such concerns.

The investigation shows that the Top Secret America created since 9/11 is hidden from public view, lacks thorough oversight and is so unwieldy that its effectiveness is impossible to determine.

It also is a system in which contractors are playing an ever more important role. Of 854,000 people with top-secret clearances, the Post estimates 265,000 are contractors. There is no better example of the government's dependency on them than at the CIA.

Private contractors working for the agency have recruited spies in Iraq, paid bribes for information in Afghanistan and protected CIA directors visiting world capitals. Contractors have helped snatch a suspected extremist off the streets of Italy, interrogated detainees once held at secret prisons abroad and watched over defectors holed up in Washington's suburbs. At Langley, Va., headquarters, they analyze terrorist networks. At the agency's training facility in Virginia, they are helping mold a new generation of spies.

Through the federal budget process, the Bush administration and Congress made it much easier for the CIA and other counterterrorism agencies to hire more contractors than civil servants. They did this to limit the federal work force, to hire employees more quickly than the sluggish federal process allows and because they thought — wrongly, it turned out — that contractors would be less expensive.

google NOSE OUT WTC and inform yourself!

Nine years later, the idea that contractors cost less has been repudiated, and the administration has made some progress toward its goal of reducing the number of hired hands by 7 percent over two years. Still, close to 30 percent of the work force in the intelligence agencies is contractors.

"For too long, we've depended on contractors to do the operational work that ought to be done" by CIA employees, Panetta said. But replacing them "doesn't happen overnight."

A second concern of Panetta's: contracting with corporations, whose responsibility "is to their shareholders, and that does present an inherent conflict."

Or as Gates, who has been in and out of government his entire life, puts it: "You want somebody who's really in it for a career because they're passionate about it and because they care about the country and not just because of the money."

Contractors can offer more money — often twice as much — to experienced federal employees than the government is allowed to pay. And because competition among firms for people with security clearances is so great, corporations offer such perks as BMWs and $15,000 signing bonuses, as Raytheon did in June for software developers with top-level clearances.

The idea that the government would save money on a contract work force "is a false economy," said Mark Lowenthal, a former senior CIA official and now president of an intelligence training academy.

As companies raid federal agencies of talent, the government has been left with the youngest intelligence staffs ever. At the CIA, employees from 114 firms account for roughly one-third of the work force, or about 10,000 positions. Many are temporary hires, often former military or intelligence- agency employees who usually work less, earn more and draw a federal pension.

Such workers are used in every conceivable way.

Contractors kill enemy fighters. They spy on foreign governments and eavesdrop on terrorist networks. They help craft war plans. They gather information on local factions in war zones. They are historians, architects, recruiters in the most secretive agencies. They staff watch centers across the Washington area. They are among the most trusted advisers to generals leading the nation's wars.

google 911 pilots truth

So great is the government's appetite for private contractors with top-secret clearances that there are now more than 300 companies, often nicknamed "body shops," that specialize in finding candidates, often for a fee that approaches $50,000 a person, according to those in the business.

Making it more difficult to replace contractors with federal employees: The government doesn't know how many are on the federal payroll. Gates said he wants to reduce the number of defense contractors by about 13 percent, to pre-9/11 levels, but he's having a hard time even getting a basic head count.

"This is a terrible confession," he said. "I can't get a number on how many contractors work for the Office of the Secretary of Defense," referring to the department's civilian leadership.

The estimate of 265,000 contractors doing top-secret work was vetted by several high-ranking intelligence officials. The Top Secret America database includes 1,931 companies that perform work at the top-secret level. More than one-quarter — 533 — came into being after 2001; others have expanded greatly. Most are thriving even as the rest of the United States struggles with bankruptcies, unemployment and foreclosures.

The privatization of national-security work has been made possible by a nine-year "gusher" of money, as Gates recently described national-security spending since the 9/11 attacks.

Most contractors do work that is fundamental to an agency's core mission. As a result, the government has become dependent on them in a way few could have foreseen.

Last week, typing "top secret" into the search engine of a major jobs website showed 19,759 unfilled positions.

Assets and liabilities

The national-security industry sells military and intelligence agencies more than just airplanes, ships and tanks. It sells contractors' brain power. They advise, brief and work everywhere, at all hours.

The purpose: to answer any question the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff might have.

Since 9/11, contractors have made extraordinary contributions — and extraordinary blunders — that have changed history and clouded the public's view of the distinction between the actions of officers sworn on behalf of the United States and corporate employees with little more than a security badge and a gun.

Contractor misdeeds in Iraq and Afghanistan have hurt U.S. credibility in those countries as well as in the Middle East. Abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib, some done by contractors, helped ignite a call for vengeance against the United States that continues today. The shooting deaths of 17 Iraqis in 2007 by security guards working for Blackwater, since renamed Xe Services, added fuel to the five-year violent chaos in Iraq and became the symbol of an America run amok.

A defense contractor formerly called MZM paid bribes for CIA contracts, sending Randy "Duke" Cunningham, who was a California congressman on the intelligence committee, to prison. Guards employed in Afghanistan by ArmorGroup North America, a private security company, were caught on camera in a lewd-partying scandal.

But contractors also have advanced the way the military fights. During the bloodiest months in Iraq, the founder of Berico Technologies, a former Army officer named Guy Filippelli, working with the National Security Agency, invented a technology that made finding roadside-bomb makers easier, according to NSA officials.

Contractors have produced blueprints and equipment for the unmanned aerial war fought by drones, which have killed the largest number of senior al-Qaida leaders and produced a flood of surveillance videos. A dozen firms created the transnational digital highway that carries the drones' real-time data on terrorist hide-outs to command posts throughout the United States.

Nayirah Saud Nasir al-Sabah, testifying (lying) before Congress. Nijirah

The Kuwait Ambassador's daughter, coached by a Washington PR firm for $2 million, lied to the US Congress and the United Nations about the infamous "Incubator Baby" murders supposedly by Iraqi soldiers.

google incubators iraq or read the wikipedia article

Without these private firms, important military and intelligence missions would have to cease or would be jeopardized. Examples:

• At the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the number of contractors equals the number of federal employees. The department depends on 318 companies for essential services and personnel. At the office that handles intelligence, six of every 10 employees are from private industry.

• The NSA, which conducts worldwide electronic surveillance, hires private firms to come up with most of its technological innovations. The NSA used to work with a small stable of firms; it now works with at least 484 and is actively recruiting more.

• The National Reconnaissance Office cannot produce, launch or maintain its large satellite surveillance systems without the four major contractors it works with.

• Every intelligence and military organization depends on contract linguists to communicate overseas, translate documents and make sense of electronic voice intercepts. The demand for native speakers is so great, and the amount of money paid for them is so huge, that 56 firms compete for this business.

Hiring contractors was supposed to save the government money. But a 2008 study published by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence found that contractors made up 29 percent of the work force in intelligence agencies but cost the equivalent of 49 percent of personnel budgets. Gates said federal workers cost the government 25 percent less than contractors.

Follow the money

Of 1,931 companies identified on top-secret contracts, about 110 do roughly 90 percent of the work on the corporate side of the defense-intelligence-corporate world.

To understand how these firms have come to dominate the post9/11 era, there's no better place to start than the Herndon, Va., office of General Dynamics. Ten years ago, the company's center of gravity was the industrial port city of Groton, Conn., where workers churned out submarines. Today, its core is made up of data tools, such as the secure BlackBerry-like device used by President Obama.

The evolution of General Dynamics was based on one simple strategy: Follow the money.

It embraced the emerging intelligence-driven style of warfare. It developed small-target identification systems that could intercept a single insurgent's cellphone and laptop communications.

It also began gobbling up smaller companies. Since 2001, the company has acquired 11 firms specializing in satellites, geospatial intelligence, reconnaissance and imagery.

On Sept. 11, 2001, General Dynamics was working with nine intelligence organizations. Now it has contracts with all 16. The corporation was paid hundreds of millions of dollars to set up and manage Homeland Security's new offices in 2003. Its employees do everything from deciding which threats to investigate to answering phones.

The company reported $31.9 billion in revenue in 2009, up from $10.4 billion in 2000. Its work force has more than doubled, from 43,300 to 91,700 employees, according to the company. Intelligence- and information-related divisions accounted for 34 percent of its overall revenue last year.

Party atmosphere

In the shadow of giants such as General Dynamics are 1,814 small to midsize companies that do top-secret work. About one-third were established after Sept. 11, 2001. Many are led by former intelligence- agency officials who know exactly whom to approach for work.

The vast majority have not invented anything. About 800 companies do nothing but IT.

The government is nearly totally dependent on these firms. Their close relationship was on display recently at the Defense Intelligence Agency's annual information-technology conference this spring in Phoenix.

General Dynamics spent $30,000 on the event. It hosted a party at Chase Field, a 48,569-seat baseball stadium. Carahsoft Technology, a Defense Intelligence Agency contractor, invited guests to a casino night where intelligence officials and vendors ate, drank and bet phony money at craps tables run by professional dealers. McAfee, a Defense contractor, welcomed guests to a Margaritaville-themed social where 250 firms paid thousands of dollars each to advertise their services and make pitches to intelligence officials.

These types of gatherings happen every week. Many are closed to anyone without a top-secret clearance.

Such coziness worries other officials who believe the post-9/11 defense-intelligence-corporate relationship has become, as one senior military intelligence officer called it, a "self-licking ice cream cone."

Another official, a lifelong conservative staffer on the Senate Armed Services Committee, described it as "a living, breathing organism" impossible to control or curtail.

missing is part 3 - Bill Arkin "Top Secret America"

Fascism: The intertwining of the State with corporations.

What is more state than the sovereign task of security?

New office buildings of private computer-surveillance companies in Washington D.C.

http://maps.google.de/maps?ll=32.676165,-117.157785&spn=0.003919,0.006899&t=h&z=17

STASI GESTAPO Version 2.0

Washington Post Investigation Reveals Massive, Unmanageable, Outsourced US Intelligence System

An explosive investigative series published in the Washington Post today begins, "The top-secret world the government created in response to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, has become so large, so unwieldy and so secretive that no one knows how much money it costs, how many people it employs, how many programs exist within it or exactly how many agencies do the same work." Among the findings: An estimated 854,000 people hold top-secret security clearances. More than 1,200 government organizations and nearly 2,000 private companies work on programs related to counterterrorism, homeland security and intelligence in 10,000 locations. We speak with one of the co-authors of the series, Bill Arkin.

LISTEN to this (easier than reading!)

http://traffic.libsyn.com/democracynow/dn2010-0719-1.mp3

AMY GOODMAN: "Top Secret America." That's the title of an explosive investigative series published in the Washington Post this morning that's already creating a firestorm on Capitol Hill. It starts, quote, "The top-secret world the government created in response to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, has become so large, so unwieldy and so secretive that no one knows how much money it costs, how many people it employs, how many programs exist within it or exactly how many agencies do the same work."

Some of the findings of the two-year investigation include more than 1,200 government organizations and nearly 2,000 private companies work on programs related to counterterrorism, homeland security and intelligence in about 10,000 locations across the United States. An estimated 854,000 people—nearly one-and-a-half times as many as live in Washington, DC—hold top-secret security clearances. Many security and intelligence agencies do the same work, creating redundancy and waste.

The series by Washington Post reporters Dana Priest and Bill Arkin includes an online searchable database and locator map. PBS Frontline is producing an hour-long documentary on the investigation that will run in October. This is its trailer.

NARRATOR: You think you know America. But you don't know Top Secret America. We're all aware that there are three branches of government in the United States. But in response to 9/11, a fourth branch has emerged. It is protected from public scrutiny by extraordinary secrecy. Top Secret America.

WILLIAM ARKIN: This is a closed community. And since 9/11, it's become even more so.

DANA PRIEST: The money spigot was just opened after 9/11, and nobody dared say, "I don't think we should be spending that much."

NARRATOR: It has become so big, and the lines of responsibility are so blurred, that even our nation's leaders don't have a handle on it. Where is it? It's being built from coast to coast, hidden within some of America's most familiar cities and neighborhoods—in Colorado, in Nebraska, in Texas, in Florida, in the suburbs of Washington, DC. Top Secret America includes hundreds of federal departments and agencies operating out of 1,300 facilities around this country. They contract the services of nearly 2,000 companies. In all, more people than live in our nation's capital have top-secret security clearance.

DANA PRIEST: It's, again, the size, the lack of transparency and the cost. And if we don't get it right, the consequences are gigantic.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Washington Post writer Dana Priest, the trailer from the upcoming PBS Frontline documentary on "Top Secret America" that features Priest and Bill Arkin.

The investigative series is already creating waves in the intelligence community. More than two weeks ago, the director of communications for the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, Art House, sent a memo to public affairs officers in the intelligence community warning about the series. He wrote, quote, "This series has been a long time in preparation and looks designed to cast the [intelligence community] and the [Department of Defense] in an unfavorable light. We need to anticipate and prepare so that the good work of our respective organizations is effectively reflected in communications with employees, secondary coverage in the media and in response to questions," he wrote.

Well, Bill Arkin is the co-author of the piece. He's joining us now from the offices of the Washington Post in Washington, DC.

Welcome to Democracy Now!, Bill. Why don't you first lay out the scope of this series and why you started this two years ago?

WILLIAM ARKIN: Well, two years ago, Dana and I got together, and we were actually just talking to each other about various things that we were working on, and we realized very quickly that we were looking at something that was very similar and that we had both detected in our long years of work in the national security world that something had been created since 9/11 that wasn't normal, that wasn't on the books, that looked like it was a gigantic superstructure on top of regular government. And we started our investigation to try to figure out what it is that we were looking at, and here we are two years later revealing our conclusions.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about what those conclusions are. What did you find, Bill?

WILLIAM ARKIN: Well, really, the most significant thing that we found, Amy, is not that the intelligence agency or the vast homeland security apparatus does work in this field and that is—and that they are engaged in counterterrorism. Really the most significant finding, to me, is the number of private companies in America who have been enlisted in the war on terrorism and who have now become an intrinsic part of government, really where the line is blurred between government and private sector. And the fact that there are almost 2,000 companies that do top-secret work in—for the intelligence community and the military is not only surprising to me as someone who actually put together the data, but it really asks some fundamental questions about the nature of government and the nature of accountability.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about these 2,000 companies.

WILLIAM ARKIN: Well, you know, it's funny. We think of the military-industrial complex in a sort of old-fashioned way still. In fact, we don't even have an appropriate word to describe what this enterprise is today, and we've struggled ourselves to try to figure that out. You know, the military-industrial complex of the Eisenhower era was one that produced massive amounts of capital goods for the military—bombers, missiles, nuclear weapons, etc. But today's national security establishment really values information technology more than it values weapons. And really, one of the things that was most surprising to us, but maybe not so surprising given the nature of society, is that a half of the companies in this particular area are really IT companies, information technology companies, and support companies.

The domination of this world of top-secret contractors over the traditional world of the military-industrial complex is huge. And we see very clearly that the megacorporations which have always been the powerhouses in the defense industry—Northrop Grumman, General Dynamics—they are moving more and more of their business from production to the provision of services—that is, providing staffing for the government. And so, what you see is that we are increasingly a national security establishment that's producing paper rather than producing weapons. And the question is, with the production of all that paper, whether or not we have either an effective counterterrorism operation or whether or not we're even safer.

AMY GOODMAN: So, what about the privatization of top-secret information or the people around the country who have access to top-secret information, especially when they're working in a private corporation?

WILLIAM ARKIN: You know, one thing that we found in the evidence, Amy, is that people who are in business are in business. I'm not going to say that they're not good Americans, any less than we are, but it seems to me that their fundamental mission is to make money for their businesses. And that is not the same as being a public servant. And as you can see from our articles, we have quotes from all of the principals involved, on the record—Secretary Gates; Leon Panetta, the CIA director; the Director of Defense Intelligence and the former Director of National Intelligence, Admiral Blair—essentially agreeing with us that this crazy, out-of-control system accreted after 9/11, and here, two years into the Obama administration, it is essentially in the same form that it was when the Bush administration left office. But there is something fundamentally wrong in America if you have people who are working in a for-profit environment caring for our national security and engaged in what we consider to be the inherent functions of government.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, it is amazing that there are more people who have top-security clearance in this country than live in Washington, DC—more than 850,000 people.

WILLIAM ARKIN: Well, it is. It's a good comparison. But I also think that what we find is that, more and more, Washington is not just the hub of government, but it is also the hub of this sort of intelligence information enterprise. You see gigantic companies like SAIC and Northrop Grumman moving their headquarters from California to the Washington, DC metropolitan area, and you know that with that comes not only thousands of workers and thousands of people whose job it is to secure contracts to do government work, but also the vast infrastructure that is required in order to secure the secrets and to do all of those things that are necessary in order to be in this hidden world. And so, more and more is being concentrated in Washington. And that's undeniable. We show it very clearly in our series, and the data really backs it up. And I think it's probably part of why there's such an enormous groundswell throughout the United States that is so anti-Washington these days.

AMY GOODMAN: Bill Arkin, what's a Super User?

WILLIAM ARKIN: Well, what we discovered in the course of our investigation is that not only are there top secrets, but there are various compartments above the level of top secret which are utilized by each of the intelligence agencies and the military commands to compartment what they do. And intrinsically, that's supposed to be to protect information, but in reality, what it does is it keeps programs from being revealed to other agencies. And in theory, above it all is supposed to be the Director of National Intelligence, an office created in 2004 to finally solve the problems of 9/11. But what we found was that even the Director of National Intelligence and even the Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence, the top intelligence official in the government, that they don't have full visibility on each other's programs, and they don't have full visibility on everything even within their own agency.

And there's this thing called Super Users, people who are designated specially who have the ability to reach into all of the programs of all of the government. They actually have special logins. They actually have special computers. And there's only a few dozen of them, as far as we can determine, throughout the entire government, only a half-dozen or so in the Defense Department and only a half-dozen in the Director of National Intelligence. And we've spoken to some of those Super Users who themselves say, "I don't have enough hours in the day to look at all the programs of the US government. I don't have enough—I don't have enough time to read all of the material that I am authorized to read." And so, you can really see in a very vivid way the dysfunction of government through this little anecdote.

AMY GOODMAN: Bill Arkin, talk about the warning, the letter that was sent around to the intelligence community from Art House—and explain who he is—warning them of this series of pieces that you and Dana Priest are doing.

WILLIAM ARKIN: Well, let me just make it clear, Amy, we've been working on this for two years. We've been engaged in interviewing people from the government and inside this world for two years. We've conducted over a thousand interviews, talked to hundreds of people, many multiple times. They were well aware of what we were doing, and we formally briefed them about this earlier this year. So for them to come out at the eleventh hour and somehow say that they are alarmed by what we're going to put out, to me, seems to be classic cover-your-ass. I can't take it in any other way, because we ourselves have gone through a massive internal review process, both fact checking and also looking at anything that could be detrimental to the national security interest and to the national interest, and I'm completely confident that we've done a rigorous job. I'm completely confident, through the use of numerous outside counsels at the Washington Post, people who are insiders to the system, helping us to make sure that we were able to produce the most granular picture we possibly could of this gigantic organization, but yet at the same time not put anybody's life at risk. And I have to say at this point, I feel like the Washington Post has a better understanding of this overall problem than the government does.

AMY GOODMAN: What is it they did not want you to print, Bill?

WILLIAM ARKIN: Well, they always don't want you to do whatever it is that's going to bring them—you know, that's going to disrupt their day. You know, the government, we asked them repeatedly to give us specifics, to tell us what it is that they didn't want us to show. And only one government agency was actually able to come back to us and specifically explain to us why they didn't want us to reveal something, and they made a reasonable argument to the editors, and the editors decided that we wouldn't.

This is such a rich area that we felt that really to diminish it by somehow not looking at these requests from the government seriously was a mistake. We're giving you information on 1,931 corporations, on 1,271 government entities across forty-five different departments and agencies. I mean, this is an enormous amount of information. And Secretary Gates himself said to us in an interview that he can't even get this type of information about his own office and who contracts all of the contractors within his own office. People recognize that this is a problem, and I think that the Washington Post should really be given an enormous amount of credit for putting the resources into this over a two-year period in order to present something that I hope will be the foundation of a new national debate about this whole question.

AMY GOODMAN: Bill Arkin, what's Liberty Crossing?

WILLIAM ARKIN: Liberty Crossing is the name, the nickname, for the new complex of buildings that has gone up in McLean, Virginia, that is home to the Director of National Intelligence, the CIA's National Counterterrorism Center, other counterterrorism task forces, and the National Counterproliferation Center. We highlight the buildings around Washington that have been created since 9/11, because we thought that it was a very tangible representation of government. It's often hard to really talk about government in terms of money, because the billions, after a while, begin to just glaze over. But we thought—you know, our approach was going to be, we know that everything that happens happens somewhere, and we're going to find out where it happens. And lo and behold, as we began to map this alternative geography of America, one of the things we discovered was that these guys have been on a fabulous building spree since 9/11. There have been over thirty-three buildings in the Washington, DC area alone, encompassing 17 million square feet, which is four times the size of the Pentagon, and there are more underway. The NSA and others are building and planning to build even more office space. So the reality is that—I think in my research I found that there was only one civilian agency that's had the privilege of building a new headquarters since 9/11 in Washington, and that's the Department of Transportation. But this is a very tangible way of seeing this in your backyard, in reality, in a real physical location.

And one of the phenomena that is also associated with 9/11 is that these locations, like Liberty Crossing, are undisclosed locations, meaning you can't look them up in a phone book. It has a cover address. It's not publicly bragged about, in terms of where it is, although it's obvious where it is to anyone who goes by. And that in itself is sort of an odd manufacture from 9/11, which is that these government agencies, on their own, with really no consideration of national security, can just decide what's going to be disclosed, what's going to be undisclosed. And as far as I can see, it's random to the agency and its power, and it has nothing to actually do with the security of the buildings or the people who work inside them.

AMY GOODMAN: The National Geospatial Intelligence Agency, the new $1.8 billion headquarters, the fourth-largest federal building in the area, in Springfield, right near Dulles Airport?

WILLIAM ARKIN: No, in Springfield, Virginia, it's down south near Fort Belvoir. This is a gigantic facility that's going to—that's going up right now. It's going to house 8,500 workers of the

National Geospatial Intelligence Agency. I mean, they are going to leave their older buildings that are scattered throughout Washington. But you know what? They're going to be in well-appointed offices, and they'll be in one facility in Washington, and they will obviously, I assume, be able to do their work better. But it's just one of many. It's just one of many agencies that probably most Americans have never heard of within the national security and intelligence establishment. And as we found, you know, there are thirty-nine new construction starts this year alone nationwide of buildings going up for various pieces of the intelligence, homeland security and military communities.

AMY GOODMAN: The growth of the military budget, Bill Arkin, since 9/11?

WILLIAM ARKIN: Well, you know, it's hard to say even what we spend on national security anymore, Amy. I guess we say we spend a half-a-trillion dollars now on national security. But with supplemental budgets and secret budgets and all that, I mean, it's really impossible to be able to put a true figure on it. And more importantly, it's really impossible to gauge where this money is actually going and how effective it is. We've talked to people on the Hill who have said to us that the budget documents get thinner and thinner as the budget gets bigger and bigger. There's no way that Capitol Hill has the resources or the ability to oversee all of this activity. And all sorts of workarounds and devices have been created since 9/11 to essentially put as much as possible into secret programs or off-the-books programs so that they're beyond scrutiny. Maybe there'll be eight people in the Congress who have the authority to see the information, but, you know, that's not oversight as it's written in the Constitution. Those are people who are co-opted into the system. And I think that really this is an issue that we, as Americans, need to ponder, that we have created a government apparatus that really does not comply with our very precept of the balance of powers. And that's something that I hope that our series will provoke Congress to take a hard look at, in terms of thinking about better ways in which it can exercise its oversight responsibilities over the executive branch.

AMY GOODMAN: Bill, you've been doing this kind of work for years. What were you most shocked by in this latest investigation?

WILLIAM ARKIN: I remember having a conversation with Dana, my writing partner, in the summer of 2009. We had sort of started by looking at the government and then shifted our attention to looking at the contracting base. And I said, "Wow! There's 200 companies that do top-secret work for the government." And now we're at 2,000. I mean, it is the sheer magnitude of it, Amy, that is stunning. And to me, you know, it's not that there might not be redundancies that are necessary or that there might not be overlap which is necessary and disparate departments doing disparate things.

And many of the conclusions that we draw, I think, are ones that your viewers and listeners would accept readily and are part of their normal discussions of government. But the truth is that no one really has a handle on it all. No one really does. We've talked to the people at the highest level. We've talked to the principals involved, and they have all readily admitted that, yes, this ad hoc crazy system was created after 9/11. We threw money at the problem. We did it the American way, Admiral Blair said to us. You know, if it's worth doing, it's worth overdoing. I mean, ha ha, but the truth of the matter is that now we're two years into the Obama administration, and the basic system really has not been reformed at all.

AMY GOODMAN: Lay out for us what we will see over the next two days—this is a three-part series—and also the database that you have collated. What is online at washingtonpost.com?

WILLIAM ARKIN: Well, this is a very rich digital journalism project. I would almost go as far to say that this is a digital product with a small print component to it. As much as the Washington Post has allocated five pages to the newspaper today to our first in this series, the online presentation includes a link analysis application, which will allow you to look at government agencies and look at functions and see how many contractors work for them at the top-secret level and at how many locations and to look at some of the featured companies that we discuss in the article series and look at who they work for and some of their locations. There's also a mapping application that allows you to delve into the presence of Top Secret America in your own community. And then there is a profile of each of those 3,000-plus entities, where you can look in more detail at their revenue, the size of the companies, and what it is that they do in this field.

So we've provided, as is the nature of the internet, the actual backup material to do it. But it wasn't a second thought to the stories. It wasn't like we wrote stories and then said, "Let's put a web presentation together." From the very inception of this project, we have worked in unison with the website, and we've had a team of over thirty people working with us, and that's an enormous amount of resources these days in the mainstream media, to be able to have really what we consider to be the future of investigative journalism displayed in these various multimedia ways with documentary footage, with photo galleries, with a database that's searchable. We have a Facebook page. And there is a URL, topsecretamerica.com, where you can see our blog that'll launch today and that we'll be starting to write on on Thursday, as well as online discussions and other comments and commentary from our readers.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Bill, I want to thank you very much for being with us. Bill Arkin, a reporter for the Washington Post, co-authored this investigative series that has just been released today in the Washington Post called "Top Secret America." We'll link to it at democracynow.org

LISTEN to this (easier than reading!)

This is an authentic poster from the 1930s!

Top Secret America | Cash cow for contractors

topsecretamerica.com

By Dana Priest and William M. Arkin

The Washington Post

The top-secret world the government created in response to the Sept. 11 attacks is so large, so unwieldy and so secretive that no one knows how much money it costs, how many people it employs, how many programs exist or how many agencies do the same work.

These are some of the findings of a two-year investigation that discovered what amounts to an alternative geography of the United States, a Top Secret America hidden from public view and lacking in thorough oversight. After nine years of unprecedented spending and growth, the result is that the system put in place to keep the United States safe is so massive that its effectiveness is impossible to determine.

The investigation's other findings:

• Some 1,271 government organizations and 1,931 private companies work on programs related to counterterrorism, homeland security and intelligence in some 10,000 U.S. locations.

• An estimated 854,000 people hold top-secret security clearances.

• In the Washington, D.C., area, 33 building complexes for top-secret intelligence work are under construction or have been built since September 2001.

• Many agencies do the same work, creating redundancy and waste. For example, 51 federal organizations and military commands, operating in 15 U.S. cities, track the flow of money to and from terrorist networks.

• Analysts who make sense of documents and conversations obtained by foreign and domestic spying share their judgment by publishing 50,000 reports each year; many are routinely ignored.

These issues greatly concern people in charge of the nation's security.

"There has been so much growth since 9/11 that getting your arms around that — not just for the DNI (Director of National Intelligence), but for any individual, for the director of the CIA, for the secretary of defense — is a challenge," Defense Secretary Robert Gates said.

In the Defense Department, where more than two-thirds of intelligence programs reside, a handful of senior officials — called Super Users — even know about all the department's activities. But as two of the Super Users indicated, there is simply no way they can keep up with the nation's most sensitive work.

"I'm not going to live long enough to be briefed on everything" was how one Super User put it. The other recounted his initial briefing: Program after program began flashing on a screen, he said, until he yelled "Stop!"

Asked last year to review the method for tracking the Defense Department's most sensitive programs, retired Army Lt. Gen. John Vines said, "I'm not aware of any agency with the authority, responsibility or a process in place to coordinate all these interagency and commercial activities."

The result, he added, is that it's impossible to tell whether the country is safer.

Gates said he does not believe the system has become too big to manage but that getting precise data is sometimes difficult. He said he intends to review intelligence units in the Defense Department for waste.

CIA Director Leon Panetta said he's begun mapping a five-year plan for his agency because the spending since 9/11 is not sustainable. "Particularly with these deficits, we're going to hit the wall. I want to be prepared for that," he said.

Before resigning as director of national intelligence in May, retired Adm. Dennis Blair said he did not believe there was overlap and redundancy in the intelligence world. "Much of what appears to be redundancy is, in fact, providing tailored intelligence for many different customers," said Blair, who expressed confidence that subordinates told him what he needed to know.

854,000 on a mission

Every day, 854,000 civil servants, military personnel and private contractors with top-secret security clearances are scanned into offices protected by electromagnetic locks, retinal cameras and fortified walls.

Much information about this mission is classified. That is one reason it is so difficult to gauge the success and identify the problems of Top Secret America, including whether money is spent wisely. The U.S. intelligence budget is vast, publicly announced last year as $75 billion — 2 ½ times the size it was on Sept. 10, 2001. That doesn't include many military activities or domestic counterterrorism programs.

At least 20 percent of the government organizations that exist to fend off terrorist threats were established or refashioned after 9/11. Many that existed before grew to historic proportions as the Bush administration and Congress gave agencies more money than they could spend responsibly.

Nine days after the attacks, Congress committed $40 billion beyond what was in the federal budget. It followed that up with an additional $36.5 billion in 2002 and $44 billion in 2003. That was only a beginning.

Twenty-four organizations were created by the end of 2001, including the Office of Homeland Security and the Foreign Terrorist Asset Tracking Task Force. In 2002, 37 more were created to track weapons of mass destruction, collect threat tips and coordinate the new focus on counterterrorism. That was followed the next year by 36 new organizations; and 26 after that; and 31 more; and 32 more; and 20 or more each in 2007, 2008 and 2009.

In all, at least 263 organizations have been created or reorganized.